- Home

- Cynthia Voigt

Glass Mountain

Glass Mountain Read online

Glass Mountain

Cynthia Voigt

Copyright

Diversion Books

A Division of Diversion Publishing Corp.

443 Park Avenue South, Suite 1008

New York, NY 10016

www.DiversionBooks.com

Copyright © 1991 by Cynthia Voigt

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

For more information, email [email protected]

First Diversion Books edition March 2017

ISBN: 978-1-68230-160-9

1

Valentine’s Day

We are none of us what we seem.

That was my thought as I stopped on the landing, a thought to which I quickly added, Except for those of us who are exactly what we seem. The mirror became a full-length portrait.

I looked just right—not too handsome. Realistically handsome, plausibly handsome, broad shoulders, good cheekbones, strong eyebrows—I looked like some dark, sleek animal, a panther, maybe a lynx, or tiger. Not one of those wispy zoo animals but a National Geographic photograph—the beast in his habitat. Rude good health, brute strength, caught on the prowl.

No matter how I moved, I couldn’t bring the third staircase into the portrait. Degas might have brought all the background in by distorting the point of view, Rembrandt might have suggested it in the shadowy darkness behind the illuminated figure, but only Picasso in his cubist period could have painted the portrait truly.

I went on down.

In the kitchen I put the day’s message onto the answering machine. “You have reached the Mondleigh residence,” I spoke over the tiny grate. Who knows how these devices work? And until they don’t work, who cares? “Please leave your name and telephone number, so that your call can be returned.” I looked up at the calendar and added a personal touch, “A good Saint Valentine’s Day to you.”

The machine reset itself with a busy whirring sound and I played the message back, to be sure it had recorded properly, and to enjoy the sound of my voice. Everything was as it should be.

Taking up a scarf from the chair, I went back along the hall, punched in the alarm code, and stepped into the vestibule. The leaded glass door locked itself automatically behind me. I opened the wooden front door, pulled on my gloves, and stepped out into the sunlight.

At midday, even the city air was sweet with the promise of spring, spring coming, soon now. I could taste that promise behind the damp chill of winter and the perpetual New York fumes. It was there, spring’s sweetness, like the perfume of a woman who has just left the room, the perfect woman and you may never meet her. But you know—as you walk into the room and catch the last, faint, already fading whiff of her presence—that if you do, she will enchant you. And have you for life. Like any sensible man, you are both terrified and eager.

I turned east, away from the park, then north along Madison among the minks and poodles, the sports satchels and portfolios. I turned east again on Eighty-Seventh, across Park, across Lexington, down toward the river, to the Wilshire Gallery.

The Wilshire has taken its lesson from the Guggenheim—broad spaces where the walls flow as smoothly as the light from room to room, each painting isolated. I walked slowly around, as if I were considering the works seriously. This was a bridge-and-rooftop painter, a student of angles, whose palette ranged from muddy black to muddy white, with brief stopovers at muddy gray and muddy brown. The red signature—NEMO—beaconing out of every canvas, suggested a flawed sense of the place of the artist in society.

One painting halted me: a three-dimensional rectangle the color of muddy gold floated on a muddy green background. When I moved close to the canvas, I could make out thick shapes on the rectangle, as if letters had been stamped into it. A K or maybe it was an R, or both? Further on a GE, an S at the end, unless it was an 8, but I thought I understood.

“You think it’s a joke?”

I turned at the man’s voice. He was in his late fifties, a pale fleshy face and shrewd eyes, a blue blazer over a blue turtleneck atop Royal Stewart trousers; his pinky ring glittered with a row of diamonds.

“If you don’t mind my asking,” he said.

“I don’t mind,” I said.

“What would you say, is it worth nine thousand dollars? I can’t tell: is it a sound risk?”

“A sound risk?”

“They keep telling me, ‘Invest in art, you can make a killing,’ but I don’t believe them, who can believe them? Property’s what I know, and I know how that works. I look at a building, say—walk around in it, get the feel of it—and I know. You know? In my gut.” He jabbed a finger at his stomach. “I’d be happier with gold. Wouldn’t you?”

“Gold always appeals,” I said.

“That’s what I told ’em, the whole crew of them. ‘Nobody ever lost his shirt in gold,’ I said. And they sneak looks at one another as if I was crazy…and I’m the one with the money. I could buy and sell all of them and their business too, if I wanted. Which I don’t. Experts, I ask you. What are you in? If you don’t mind my asking.”

I didn’t mind. “This and that,” I told him. “Stocks and bonds. Domestic services.”

“Domestic services, is there money in that?”

“You’d be surprised.”

“So you’d advise me not to buy this.”

“I’m not advising anyone.”

“Yeah, I hear you, but just answer me this. Are you going to be picking it up?”

I shook my head.

“I rest my case.” He was pleased with himself, pleased with me. “I’m glad I ran into you, young fellow. You look like someone who knows what’s what, that’s my gut reaction. Those guys don’t give me the same good feeling. But they can’t run me in circles, I’ll let them know that.” He stepped up close to the picture, leaned his face into it. “Because this stuff is junk. I don’t know anything about art, but I know garbage when I see it. If you don’t mind my saying so.”

He departed abruptly. I figured he was going off to blister his financial advisers, and they probably deserved it, if for no better reason than breaking the basic law of economy that states that the tune the piper plays is called by the man who pays. Or woman.

I took the broad staircase up to the second floor, following my own plans for the day. Mr. Plaid Pants had been a diversion, not a distraction.

I recognized her right away. She sat on a low bench, facing a canvas that splayed its angularity over half the long wall. She wore a broad-brimmed hat, and her tawny hair brushed at her shoulders. She was alone.

I didn’t rush at her. I don’t rush women. It’s disrespectful to them, and to me too, as if the only way I could win a woman is by the emotional equivalent of a football tackle—knock her sideways, off balance, breathless, and down. As if the only way I could attract her is for my pheromones to grab her hormones by the throat and shake them into mindlessness, and then she will take me to herself. Which otherwise she wouldn’t think of doing.

Slowly, I circled the room. She paid no attention to me. I wondered what she was thinking. Was she trying to picture the painting on a particular wall, immersing herself in a decorating dilemma? Did she see something in the canvas that made life palatable, comprehensible, endurable? Or did she see something that troubled her spirit and was she concentrating on capturing the idea before it was lost to her? Was she killing time while awaiting a friend, a lover, a husband, awaiting an appointment, or the time when she could have her next meal? Wh

ich is at least doing something, something to do. Or was she waiting for the chance of me?

Taking a seat on the bench, I kept my eyes on the painting, first, then turned for a brief look at her, an unaggressive look, unassuming, a stranger’s glance at a nearby stranger. Her hair was entirely lovely. It seems to me possible to love a woman for the beauty of her hair.

“Strength and boldness,” I said, my attention back on the picture. “It certainly has those. Are you thinking of buying it?”

We sat side by side, like the profiled emperor and his consort of a Byzantine coin.

“No.” She shook her head and her hair swung like heavy cloth.

After a while she asked, “Are you?”

“No.” Like her, I didn’t say that I couldn’t afford to hang twelve thousand dollars on my walls.

After another little quiet time, during which she sat without moving, she added, “I have two Nemos already.”

I followed the pace she set and waited before I answered. “They may prove a good investment.”

Then she did turn to look at me. “I don’t buy art as an investment.”

“Good,” and I smiled entirely frankly. “Good for you.” She had perfect teeth. “Maybe you can answer a question. The painter’s name—what do you call it, a nom de palette? Do you know if it’s the classical reference? Or the Victorian?”

“That, I won’t tell you.”

Not can’t, won’t. If not Homer or Verne, then what? I wondered; there was some secret she wanted me to know she was keeping. I asked her to lunch.

She hesitated, itself a compliment. She took a pair of leather gloves out of her purse and held them in her hands. “Are you married?” she asked.

This is a tricky question and when it gets asked early on it’s hard to know how to respond. “Yes,” I hazarded.

The wrong answer—although it might be that no would have been equally wrong. She might have chosen a question which, no matter how I answered, would become her reason to refuse me.

“I make it a rule never to go out with married men, not even for lunch.” She rose, and I rose with her. She turned and went down the staircase. She knew I was watching: her head turned to one side and the other as she descended, so her hair could swing beautifully.

I sat down again, alone, waiting and thinking.

Three women in their early twenties chattered together as they came up the stairs. Over from First Avenue, I guessed, one a student, the others salesgirls in boutiques, and I would have guessed, if asked, that they were roommates. Nobody asked but I guessed anyway.

I didn’t approach them, although the tallest looked queryingly at me. They were on a lunch-hour visit. The student wore a pair of wing-tipped shoes, which gave her legs a wonderfully gamine look; one salesgirl wore plain low heels, which emphasized her wonderfully slender ankles; and the other wore equally plain pumps with a higher heel, which emphasized the wonderful plumpness of her calves.

Women, I thought, are more at ease than men with variety of style or with variety of manner, more at ease with variety. In literature and art, and especially in the mythology of the arts, the heroic man is a raging individualist, but perhaps it is his rarity that makes him heroic. Women, I think, are the natural anarchists.

I sat for an hour or more, but the only other woman to catch my eye—her emerald earrings swung in the light—was joined by a stout and prosperous overcoat whose fingers on her elbow left no doubt about who she was lunching with. She greeted him gladly and leaned forward for a welcoming kiss; her emeralds winked at me like conspiring little devils. When I was hungry enough, I descended the stairs to claim my coat. On impulse, I asked the gallery attendant if she was free for lunch. She considered me. “Are you married?”

“Why no,” I hazarded.

“I’m sorry,” she said, and seemed sincere. She held the heavy glass door open for me. “I make it a rule never to accept invitations from unmarried men.”

2

I Meet Her

I was welcomed at the restaurant in the language particular to upscale New York waiters—part French, part Irish, with something of Italian liquidity to it, especially around the gestures—and seated without delay. I asked for a glass of the young Sangiovese and on the waiter’s recommendation ordered veal; with everything settled, I sat back and looked around the room.

Besides myself, she was the only person eating alone. It’s unusual to see a woman eating alone in such a restaurant, especially lunch, especially a young woman. A bright metal bucket was set beside her, the swathed bottle resting a little askew, the tulip glass half-filled with champagne. She seemed lost in contemplation of the glass and her hands. She looked barely old enough to be drinking legally, if she was in fact old enough.

There are millions of people in New York on any working day. Over half of them are women, and perhaps four percent of those have money of their own, and maybe ten percent of those—a tenth of that twenty-fifth of that half—are what might be called monied. I studied the solitary young woman.

She had a fresh-from-the-salon look, everything about her carefully in place, everything new and expensive. Because her head was bent, I couldn’t see much of her face, just a part of a cheek, the chin line, half of a bright-red mouth, and the rest a long tumble of curls. The wild gypsy look, which women seem to like on themselves, was at odds with her baby-blue dress with its wide sailor-style white collar and long sleeves. The red lipstick matched the red piping on collar and cuffs, matched the red nail polish, matched the red boots visible under the tablecloth. She looked like a doll somebody had dressed up to go out with. I wondered if she had been stood up for a lunch date; she had a stood-up look to her. Her cheeks were pink, but whether from blusher, champagne, shame, or chagrin I had no way of knowing.

A plate was put in front of her and she toyed with her food but didn’t eat much. Her glass was kept full. She kept emptying it. The bold nails were at odds with the hesitant movements of her ringless hands.

I didn’t stare at her as openly as it sounds. I drank my wine, ate my own lunch, looked around the room, thought my thoughts. I was savoring my coffee when she asked for her bill. Her red purse looked unworn, stylish, too small to carry much more than comb, lipstick, powder, and a couple of credit cards.

I paid cash, as always, and tipped generously. I was in no hurry to leave, so I watched her carefully sign her receipt, carefully slide out from behind the table, and walk carefully to the door to the coatroom. It was a sailor dress she was wearing. Between the shapeless blouse, the full skirt, and the boots, her figure was effectively concealed. She was short, I could see that, but I doubted my own eye because in everything else—hair, makeup, dress, footwear—her appearance was designed for a tall woman, a tall and stylishly thin woman, most certainly a woman old in experience. This girl suggested innocence. But the coat she accepted was a long, dark, worldly mink, and she puzzled me.

Perhaps she had no mother. Perhaps her mother had bad taste, or kept herself young by keeping the daughter younger. Or perhaps this young woman was convinced that as long as she spent a lot of money, she was getting her money’s worth.

I didn’t follow her out of the restaurant. I wasn’t that puzzled; she was only a girl. It was, however, not many minutes later that I stood outside the entrance, looking up and down the street, assuring the waiter that yes, my meal had been delicious, and yes, I had tried the veal, which had been all he had promised. The young woman in mink was, I noticed, making her slow way down the street.

While we watched, she wobbled over to a set of scrubbed steps and sat. A nanny wheeling her pram toward us made a wide circle around the hunched figure.

“She’s never been in the restaurant before, not that I remember,” the waiter said. “But I mean, look at her. She’s not a woman you’d remember.” He had forgotten his accent.

After a brief rest, she pulled herself erect and hesitated. A man walking toward her looked at her, and she looked down at the ground before moving on her wobbly way.

He gave her the kind of smile that explains why women have taken up martial arts and approached closer.

“What a city this is,” the waiter remarked, accent remembered. “Terrible, yes?”

That would have been a long argument, so I just nodded my head as if I were agreeing and buttoned my coat. She had crossed to the opposite side of the street and the man had started to cross to intersect her but, seeing me, veered off by the time I overtook her.

I put a gloved hand on her arm—not the upper, intimate arm, but the lower arm, just above the wrist, and just the slightest of touches. I spoke in my plummiest voice. “Excuse me, miss?”

She stopped. Her quick glance had nothing but alarm in it. She wasn’t a girl. She was old enough to be wary of chance encounters, and her face had none of the unfinished look of girlhood. “I’m sorry,” she said, “I’m on my way…” She spoke with slow self-consciousness, and she swayed gently where she stood.

“You’ve had too much to drink,” I said, nonjudgmental, impersonal.

She moved to pull her arm away but the gesture almost unbalanced her, so I held on. Fur is slippery, not easy to grip with gentlemanly firmness.

“I don’t think I know you.” She spoke almost in a whisper. “I’ll scream for help.” She looked carefully at me. “Do I know you?”

“I was in the restaurant. Let me get you a cab. Really, I’m safe.” There was no reason for her to believe me.

She drew herself up. Even in the high-heeled boots she didn’t reach my shoulder. “I don’t want a cab. Thank you.”

“You can’t wander the streets like this.”

“A cab would take me home.”

“Home is the best place for you.”

She shook her head, then reached out to steady herself on my arm. “I’ve had too much to drink,” she said. “I need to sit down.”

I raised my hand to signal an approaching cab. “That’s right, you do. You’re absolutely right. That’s very sensible of you.” The cab pulled up beside us, halting traffic. I opened the door for her. A few horns protested the inconvenience. She hesitated.

The Runner

The Runner By Any Name

By Any Name Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do?

Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do? Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things: Mister Max 1

Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things: Mister Max 1 The Wings of a Falcon

The Wings of a Falcon Bad Girls in Love

Bad Girls in Love Toaff's Way

Toaff's Way Building Blocks

Building Blocks Orfe

Orfe Tell Me if the Lovers Are Losers

Tell Me if the Lovers Are Losers It's Not Easy Being Bad

It's Not Easy Being Bad The Book of Kings

The Book of Kings Dicey's Song

Dicey's Song A Solitary Blue

A Solitary Blue Tree by Leaf

Tree by Leaf Sons From Afar

Sons From Afar Teddy & Co.

Teddy & Co. Jackaroo

Jackaroo Elske

Elske Izzy, Willy-Nilly

Izzy, Willy-Nilly Come a Stranger

Come a Stranger Mister Max: The Book of Secrets: Mister Max 2

Mister Max: The Book of Secrets: Mister Max 2 Seventeen Against the Dealer

Seventeen Against the Dealer The Callender Papers

The Callender Papers The Vandemark Mummy

The Vandemark Mummy Tale of Birle

Tale of Birle Glass Mountain

Glass Mountain The Tale of Oriel

The Tale of Oriel The Book of Lost Things

The Book of Lost Things The Book of Secrets

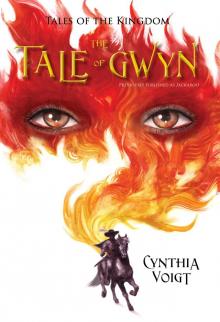

The Book of Secrets Tale of Gwyn

Tale of Gwyn