- Home

- Cynthia Voigt

It's Not Easy Being Bad

It's Not Easy Being Bad Read online

Contents

1. Miss Very Unpopular and Miss Almost As

2. Can Bad Eggs Make Good?

3. One (bad) Egg, Scrambled

4. Junior High Justice

5. The Revenge of the Ant People

6. The Cheese Stands Alone

7. What Now? What Next?

8. What If—?

9. Can Unpopular People Have a Popular Opinion?

10. Lose Some, Win Some

11. California, Here I (don’t) Come

12. Margalo Solo

13. One (bad) Egg, Poached

14. Godzilla vs Thumbelina

15. Two (bad) Eggs, Sunny-side Up

For Molly Hartman

(Bad Girl, Ret.)

1

Miss Very Unpopular and Miss Almost As

“What’s so bad about me?” Mikey Elsinger demanded.

Two weeks after the start of seventh grade, she and Margalo Epps were wandering around outside West Junior High School, with maybe five minutes, maybe seven—or maybe only four minutes left until the bell rang to summon them to homeroom and the start of another day’s uneasy boredom.

Margalo reminded her, “You don’t want to be friends with any of these people.”

Mikey just repeated her question. “Do you know what it is about me?”

Margalo did have a few ideas on the subject. They’d been best friends since the first day of fifth grade, and she’d seen the effect Mikey had on other people—sort of like the effect Godzilla had on Tokyo. But Margalo also knew human nature and she had figured out by now that when somebody asks you what’s wrong with them, the thing they really don’t want to hear about is: what’s wrong with them.

Besides, she didn’t think the things other kids didn’t like about Mikey were wrong things. They were just Mikey, like her thick braid and her short, solid, quick-moving body, the bossiness, the never-backing-down, the not-listening, the only-seeing-things-her-own-way. Mikey was a one-way street, with a high speed limit. No wonder her life was full of collisions. Margalo really admired Mikey, and envied her, too. Sometimes. About some things.

The two girls wandered up to the main entrance and wandered into the building; they drifted down a broad hallway crowded with seventh and eighth graders, leaning against lockers, clustered in small circles, talking about sports and TV shows, griping about parents, all the time watching one another watch one another. Nobody paid any attention to Mikey and Margalo. Just about anything, two gerbils, a pair of potatoes rolling down the hall, anybody was more interesting than Mikey and Margalo. Becoming nobodies as soon as they walked into the first day of seventh grade was one of the things Mikey and Margalo liked least about junior high.

“Sometimes,” Margalo said to Mikey as they moved along unnoticed, “I feel like I come from another planet.”

“They’re the ones from another planet,” Mikey said. “I hope a meteor gets it.”

Turning a corner, they entered the broad central hallway, its walls painted a soothing beige, its floors a thick, sound-muffling linoleum. Here, throngs of seventh and eighth graders moved in both directions. “I asked you,” Mikey said. “Don’t tell me you don’t have ideas, because I know better.”

West Junior High was all on one level, with the cafeteria, auditorium, and library located in the center of the building. Because it was central, the library had no windows. But it did have tables, and a thick carpet if you preferred sitting on the floor. It was the library they wandered into now. “I asked,” Mikey said again.

“Well,” Margalo answered slowly, trying to think of what she might say that wouldn’t set Mikey off on a rant about how Margalo spent too much time thinking about what other people were thinking (which Mikey definitely did not do), or how people in general were chickenhearted sheep (which Mikey definitely wasn’t), the same speech Margalo had heard a hundred times before, and did not want to hear again. Even if Mikey was right, Margalo didn’t have to listen to her rant about it. “Look at it this way . . . ,” Margalo said, even more slowly, wondering how long she had before the bell rang and rescued her from this conversational predicament.

Mostly, people worked together at library tables, comparing homework, preparing excuses. A few of these people Mikey and Margalo knew from their old school. Hadrian Klenk was alone, hunched over one of the computers behind the stacks, but Ronnie Caselli was at a table with a group that also included Derry Zurlo and Tanisha Harris. Tan wore a hooded sweatshirt, which declared athletics as her interest, and Derry wore a logo-ed cotton polo like Ronnie’s, except in a different color. The new girl, Frannie Arenberg, was at the same table.

Everybody was new to West Junior High School, and Frannie was new to town, too, so she was an entirely new girl, but she was already one of the most popular seventh graders. Seeing her, Margalo was seized by inspiration. “Take Frannie,” she said to Mikey, who glared with a toothy smile at the table of girls. “You’re about the exact opposite of Frannie.”

Mikey studied Frannie, who was—like almost every other seventh-grade girl—medium tall, medium thin (or medium fat, if you wanted to put it that way), medium pretty, and nothing special except for having great hair. Frannie wore her golden brown hair long and whenever she moved her head, it swayed and flowed like hair in a TV ad. Unlike other seventh and eighth graders, except Mikey, Frannie had bangs that feathered down over her forehead. But bangs were about all Mikey had in common with the new girl. Frannie Arenberg smiled a lot, big bright smiles as if she was having a good time in seventh grade, and she laughed easily, a real laugh, not a screechy seventh-grade-girl giggle. From day one, everybody had known who Frannie was—the new girl—and everybody wanted to be friends with her.

“What’s so special about her?” Mikey demanded. She hadn’t bothered to lower her voice, so everybody sitting at that table looked up.

Mikey wasn’t about to look away from those faces.

Ronnie gave Margalo a little quick smile, the kind that doesn’t want to be smiled back at, and Tanisha raised one waggling finger to Mikey, Shame on you. Mikey flashed back an I-could-care-less smile. The rest of the girls looked blank, even Derrie, as if they had never seen Mikey and Margalo before. But Frannie Arenberg smiled right at them, her big, round, brown eyes happy to see them. She moved her chair over, offering them room at the table with everybody else.

Luckily, the bell rang.

“What’s wrong with her?” Mikey demanded as they left the library.

* * *

After homeroom, Mikey and Margalo separated for their morning classes. Margalo was in the A English section and the C math, and she felt worried to have been placed even that high in math. Mikey’s first two classes were nonability grouped, social studies and gym. Then Margalo went to her gym class, which seemed ability grouped to her, and social studies, which definitely wasn’t, while Mikey had B English and A math. They usually managed to meet up at their lockers at least once in a morning.

Not that they had anything particular to say. Just, they could have someone to talk to who wanted to talk to them. It was lucky for them that the basic organizing principle of junior high was the alphabet, because that put them in the same homeroom, the same lunch, and the same humanities seminar.

That morning, Margalo did have something to say as they clanged their locker doors open, shifting books and notebooks, checking papers. “I’m your friend,” Margalo pointed out.

“You don’t count. You like me,” Mikey explained. “I’m talking about friends, we’re in seventh grade, friends are people you go to the mall with. Not people you like. They’re people who when other people see you with them everybody thinks you’re an okay person. They’re people you act with the way I promised myself I’d never act.”

“That’s a joke,” Margalo decided.

“Friends are people to hang with,” Mikey concluded as another bell rang and they joined another surging crowd, which moved them away from one another.

* * *

The next time they met at the lockers was before first lunch. Margalo had been thinking. “People to hang out with,” she said.

“You are such a schoolteacher,” Mikey argued.

“People to hang with is, like, hanged by the neck until dead,” Margalo argued back.

Mikey knew that the person with the last word wins. “That’s what I mean,” she said.

Margalo took out her lunch bag and slammed her locker door shut. They went to the cafeteria.

Mikey did not enjoy her cafeteria lunch, a slab of meat loaf covered with brown oobleck, an ice-cream scoop of unnaturally smooth mashed potatoes, peas so pale, you knew they had spent the last days of their lives locked away in some can. Mikey swallowed quickly, with minimum mouth exposure to what she was putting into it.

“You should eat from the salad bar,” Margalo advised. Her lunch was a bologna sandwich on supermarket whole wheat bread, pale and pasty brown but an improvement over Aurora’s usual supermarket white bread. Margalo also had a banana, and there was nothing much you could do to ruin a banana, and saltines with peanut butter. Only a few seventh and eighth graders brought their lunches from home—vegetarians, kosher kids, kids with allergies. It was definitely not cool to BYO for lunch at WJHS, but Margalo’s family consisted of three sets of siblings, plus her only-child self, plus Aurora and Steven, whose marriage brought together so many people. In Margalo’s family, money was tight, so she had no choice about brown-bagging lunch.

Mikey had a choice, but she didn’t like it. “The salad bar lettuce died last week,” she told Margalo. “In some foreign country. After a long illness. Lunch is the only time I miss having my mother around, you know? That woman packed a great lunch.”

“She probably still does,” Margalo pointed out unsympathetically.

“Well, dunhh. But not for me.”

“You could pack your own lunches,” Margalo pointed out unsympathetically.

“I could. Maybe I will. If I do, don’t think I’ll share with you.”

“Okay, I won’t think it. But you will. You’ll want me to tell you how good it is.”

Mikey denied that, although she knew it was true. “Dad will tell me.”

“But you won’t believe him the same way you will me, because he’s your dad and he thinks everything you do is terrific.”

“Not everything,” Mikey said, but the protest was insincere. Her life had actually gotten a lot easier since her parents separated, and her mother moved back to the city. Everybody had benefitted from the Elsingers’ divorce. Mrs. Elsinger had a new position with improved prospects for promotion, and she didn’t have to sneak around to see her boyfriend. Mikey and her father moved out of their fancy neighborhood into a more modest house and were banking most of the child support checks into Mikey’s new college account. Even Margalo had benefitted, since Mr. Elsinger paid Aurora, Margalo’s mom, to take responsibility for Mikey until he could pick her up. Between Mr. Elsinger’s money and Sam’s Club, Aurora and Steven were getting by more easily.

Mikey pronged four peas and held up her fork. “These cafeteria lunches make an educational contrast to our home cooking,” she said, claiming, “that’s the only reason I eat them,” which Margalo didn’t believe for a minute. Mikey rotated her pea-tipped fork, studying it. “They used to put the heads of executed criminals and traitors on spikes near the Tower of London,” she told Margalo, then put the fork into her mouth. There was no need to chew. This was a mush-and-swallow eating event.

Margalo looked around the big cafeteria. Tables of seventh-grade boys, tables of seventh-grade girls, and tables where the boys and girls sat together, which meant they were eighth graders. No seventh grader was ready to eat lunch with a boyfriend or girlfriend, no matter how many hours they might spend together at the mall practically on a date.

Mikey also looked around. “Last year wasn’t like this,” she said. “I liked last year.”

Margalo was happy to share some of her ideas about the many differences between sixth and seventh grades. “Last year, with one teacher all day, in the same classroom all day, people had to act the way the teacher wanted. Now we’re split up into all different classes with different teachers so we’re on our own more. Being on our own makes most people nervous, so we band together, like in clubs.” Margalo enjoyed explaining human nature to Mikey (who wasn’t all that interested in the subject, except when it got in her way) so she added, “Besides, if you’re a club you get to exclude people.”

“We should start our own club,” Mikey said, looking around at the tables.

“A club of two?”

“You know what I mean.”

“I know what you mean to mean,” Margalo allowed. “And I don’t agree with you.”

“So what else is new?” Mikey said, to win the argument.

“Zut!” Margalo muttered, short for zut, alors!, which was French. Before school started, Mikey had decided that one thing they shouldn’t do was swear, “because everybody will expect us to be really foul-mouthed.” Margalo agreed, except, “You have to say something, sometimes, or people will think you’re a wimp.” So they were developing their own cuss vocabulary. Mikey’s grandmother in California, who dyed her hair red, used to say zut, alors! whenever Mikey captured one of her chess pieces. Mikey and Margalo put that first on their list of cuss words, followed by rats! (stolen from Snoopy), and mice! (derived from rats!), and then (by natural progression) rodents! Margalo was thinking of bunnies! She was waiting for the chance to try oh, bunnies! out on Mikey.

“Then we should be a clique,” Mikey suggested.

“Cliques have to be something people want to be in.”

“Why shouldn’t I be popular?” Mikey asked.

Margalo just shook her head. In Margalo’s opinion, the words “Mikey” and “popular” didn’t even belong in the same dictionary, much less the same sentence. Typical, normal kids were what worked in junior high, as far as Margalo could see, but she didn’t bother pointing that out to Mikey.

“Is it the way I dress?” Mikey asked.

“We never talked about clothes before seventh grade,” Margalo pointed out. “That’s another difference.”

Mikey stuck to her point. “You don’t dress like anybody else, either. Although you always look—like some model in Elle? Not like Seventeen. Like some exchange student. Or someone from another planet,” she added. “I think it’s because you’re so tall, and skinny. You look better dressed than other people, even if you do get all your clothes at thrift stores.”

“And the New-to-You,” Margalo added, ignoring the reminder that she was one of the tallest people in the seventh grade, boys included. Actually, she thought it was lucky she couldn’t afford to dress according to fads. Because of that, she dressed according to her own sense of style, wearing calf-length skirts as often as jeans, wearing blouses not T-shirts as a rule, and never cute little tees over cute little minis, even though those, like everything else, looked good on her. Mikey was short and round and already a C cup; she wore wide-legged cargo jeans and gray T-shirts, the same thing every day, her going-to-school uniform.

“Even if we dressed like them, we wouldn’t fit in,” Margalo said now. “But you could try, if you cared what you look like.”

“How do you know I don’t care?”

“Because if you did, you’d do something about it.”

“What makes you think you know all about me?” Mikey demanded. “But even if I dressed like one of the jockettes,” she said, “or, better, like a Barbie—it still—”

That picture caused Margalo to practically choke laughing. The Barbies were what they had named the girls who wore big heads of curled hair, or some other designer hairdo, like beads, any hairstyle that took hours to create. High-maintenance h

air was a hallmark of the Barbies. Also, they dressed in full skirts with wide, tight belts, shoes with spindly heels. And they wore full-face makeup, every day. Mikey didn’t even own a pair of dress shoes, or a lipstick.

“It’s not that funny,” Mikey said, and hoped the time was right to ask, “Want to trade your banana for this chocolate pudding?”

Margalo didn’t.

Mikey didn’t ask again. Instead, she explained human nature right back at Margalo. “It’s much easier for boys to be popular, because they’re almost all jocks. Even if they’re good at school, they’re still jocks first. But with girls—it’s more complicated. There are all these specialized groups, jockettes, punkers, arty-smarty types, as well as the Barbies, and let us not overlook the preppies.” Mikey stopped to think about what she had said, before concluding, “Then there’s us.”

“What about us?” Margalo asked.

“We’re some subcategory of normal,” Mikey decided. “Not regular normal. But whatever kind of normal we are—sub-, or ab-, or even super-—mostly we’re not.”

“I am,” Margalo maintained.

Mikey snorted sarcastically.

“Closer to it than you, anyway,” Margalo claimed, and then admitted, “I look closer, and how you look is what counts in seventh grade.”

Mikey went right on with her own idea. “But practically every one of us not-normals has maybe one friend. So maybe each pair of us is a clique after all. I don’t see why we can’t be. You could be wrong about something, Margalo. And I could get popular.”

“I’ll share the banana with you,” offered Margalo, who’d had a sudden glimpse of how things would be if Mikey wasn’t around to eat lunch with. “How would you go about getting popular?” she asked.

And then Mikey surprised her. “I’m going to give it more time,” said Mikey the impatient. “Think about it, Margalo, it’s taken us almost two weeks just to find our way around the building, and in sixth grade some people ended up liking us, didn’t they?”

“Everything’s different in seventh grade. Everybody. School’s different.”

The Runner

The Runner By Any Name

By Any Name Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do?

Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do? Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things: Mister Max 1

Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things: Mister Max 1 The Wings of a Falcon

The Wings of a Falcon Bad Girls in Love

Bad Girls in Love Toaff's Way

Toaff's Way Building Blocks

Building Blocks Orfe

Orfe Tell Me if the Lovers Are Losers

Tell Me if the Lovers Are Losers It's Not Easy Being Bad

It's Not Easy Being Bad The Book of Kings

The Book of Kings Dicey's Song

Dicey's Song A Solitary Blue

A Solitary Blue Tree by Leaf

Tree by Leaf Sons From Afar

Sons From Afar Teddy & Co.

Teddy & Co. Jackaroo

Jackaroo Elske

Elske Izzy, Willy-Nilly

Izzy, Willy-Nilly Come a Stranger

Come a Stranger Mister Max: The Book of Secrets: Mister Max 2

Mister Max: The Book of Secrets: Mister Max 2 Seventeen Against the Dealer

Seventeen Against the Dealer The Callender Papers

The Callender Papers The Vandemark Mummy

The Vandemark Mummy Tale of Birle

Tale of Birle Glass Mountain

Glass Mountain The Tale of Oriel

The Tale of Oriel The Book of Lost Things

The Book of Lost Things The Book of Secrets

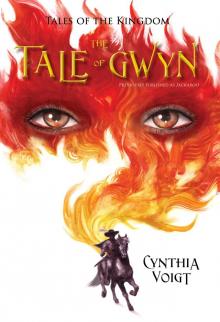

The Book of Secrets Tale of Gwyn

Tale of Gwyn