The Runner

The Runner By Any Name

By Any Name Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do?

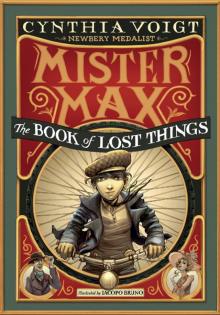

Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do? Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things: Mister Max 1

Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things: Mister Max 1 The Wings of a Falcon

The Wings of a Falcon Bad Girls in Love

Bad Girls in Love Toaff's Way

Toaff's Way Building Blocks

Building Blocks Orfe

Orfe Tell Me if the Lovers Are Losers

Tell Me if the Lovers Are Losers It's Not Easy Being Bad

It's Not Easy Being Bad The Book of Kings

The Book of Kings Dicey's Song

Dicey's Song A Solitary Blue

A Solitary Blue Tree by Leaf

Tree by Leaf Sons From Afar

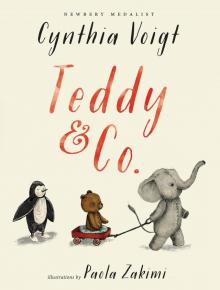

Sons From Afar Teddy & Co.

Teddy & Co. Jackaroo

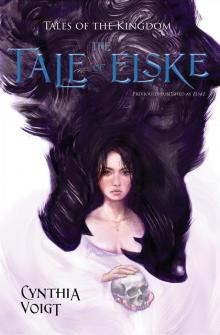

Jackaroo Elske

Elske Izzy, Willy-Nilly

Izzy, Willy-Nilly Come a Stranger

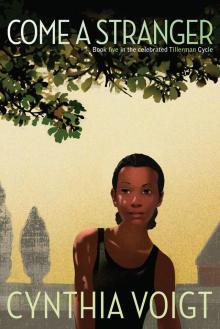

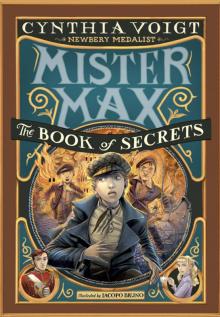

Come a Stranger Mister Max: The Book of Secrets: Mister Max 2

Mister Max: The Book of Secrets: Mister Max 2 Seventeen Against the Dealer

Seventeen Against the Dealer The Callender Papers

The Callender Papers The Vandemark Mummy

The Vandemark Mummy Tale of Birle

Tale of Birle Glass Mountain

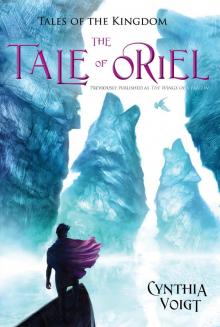

Glass Mountain The Tale of Oriel

The Tale of Oriel The Book of Lost Things

The Book of Lost Things The Book of Secrets

The Book of Secrets Tale of Gwyn

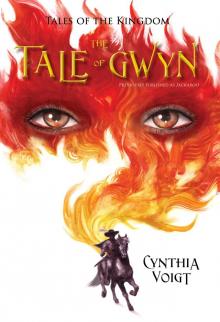

Tale of Gwyn