- Home

- Cynthia Voigt

The Wings of a Falcon Page 32

The Wings of a Falcon Read online

Page 32

“I will,” Griff said. “I promise.”

“I mean Merlis,” Oriel said.

“Oh,” Griff said.

Griff’s eyes were as brown as the earth of the southern lands. The ringing in Oriel’s ears made him almost deaf, but he saw the answer he asked in Griff’s eyes, as Griff’s mouth moved.

But her name eased him, to speak it, so as the darkness rose up Oriel greeted it with her name.

Chapter 27

HIS SLEEVE WAS WET WITH Oriel’s blood. His breast was damp with Oriel’s tears. He looked around, for help. It was Lord Haldern he saw. “Sir, send for the girl. The puppeteer. You called her Baer? In Lord Hildebrand’s territory. Near the mountains.”

Never mind how he and Beryl had last parted. Never mind his own resolution to leave her in the solitude she asked of him. She wouldn’t deny Oriel. Griff saw Lord Hildebrand’s son among the men who stood around him, where he knelt on the ground with Oriel in his arms. “Wardel, sir, can you send soldiers for her? Can you help me? She knows healing, she knows—”

The young man needed no further word. He spoke to the King’s Captain, beyond Griff’s hearing, then ran to his horse, and mounted, and turned its head to the north.

Griff struggled to his feet, Oriel a heavy weight in his arms. He thought his heart had been torn from his chest. Fear gave him the strength he needed to lift and hold his friend.

“Where—?”

He shut his voice off. It was a howl like a wolf’s that he barely kept in his throat.

He saw the Queen come forward, among her women, making murmuring noises. He saw soldiers hold a squirming man down on the ground.

Nothing to do with Griff now. Griff had only Oriel to think of. Oriel breathed, but pink foam dribbled out of his mouth.

And Beryl was not here to medicine him. Griff knew nothing of healing. He heard Lord Haldern speak, and there were tears in the man’s voice. “Take . . . my house . . . litter. . . .” Some of the words Griff could hear and some never entered his ears.

Lady Merlis, with her cold grey eyes and her long shining hair, stood beside the man the soldiers now held erect.

Servants came to hold out a litter, upon which he placed Oriel, and when the servants lifted it again he stayed with Oriel, in case his eyes might open.

He couldn’t understand what had happened. His understanding was trapped at the time when Oriel stood before the kneeling lords, about to be named Earl Sutherland.

What had happened? Oriel had stood in his slender, high-shouldered pride, drawing all eyes to him. There was that in Oriel—and had ever been, even from the first—that drew the eyes, first, and then the heart. The man of eighteen winters, who had claimed the Earldom without shedding blood, who had boldly risked everything, even the woman of his heart—he was no surprise to Griff. That man was the natural kin of the boy who came to the Damall’s island and proved stronger even than all the fear the Damall could summon onto his boys. The boy and the man had both walked on the land as if it belonged by rights in their care. The boy and the man had both stood unvanquished—aye, and untarnished, too—and always, Griff thought, worthy of his life’s service.

Grief almost knocked Griff’s knees out from under him.

Long-robed priests awaited them at Lord Haldern’s house, with their books of medicine and their pots of balms. Griff knew them for men who would do the best they could.

When Oriel lay on his stomach, the bleeding staunched by a folded cloth, Griff sat beside him on a low stool. He listened to the thready breathing—in and out. The priests came and went, to study the wound and try to pour spoonfuls of medicine down Oriel’s throat. They spread ointments on Oriel’s naked back, and his breathing halted, came fast, then steadied.

“My lord,” the priest said, a young man with yellow-green cat eyes, “will you not eat?”

It was by then dark and candles were lit. Griff shook his head, to shake away the company, to deny everything. As long as he sat beside Oriel, the breathing continued. He did not necessarily believe that if he were to leave, or to sleep, then Oriel would die. But he knew he must not move from the room.

He had no hunger and no thirst. He rose from the stool only to urinate into a bedpan, which a servant removed, or a priest, he paid no attention, for he sat hunched beside the bed where Oriel lay breathing thinly, threadily, painfully.

If Beryl would only come. If they found her she would come. She would never refuse Oriel anything. Griff had always understood that, even as he grew to know that he desired her for himself. She was the best of women. She would of course choose Oriel.

And if Beryl knew Oriel needed her skill, and help, nothing would keep her from this room. Griff knew her heart.

“My lord,” one of the servants asked. “Will you take food?”

It was growing light. Griff shook his head. He hadn’t slept, and he wasn’t tired. His will held tight to Oriel’s will. It was as if he held Oriel tethered to life, through his will. It was as if his will allowed Oriel to fly up, aloft, above the pain of flesh, so that Oriel wouldn’t abandon his body, despite the pain that tried to drive him away.

Sometime during the first day, Griff understood what had happened. He remembered Oriel’s refusal to fight to the death, and the response of the other contenders, and Tintage’s sword driving into Oriel’s back. He understood that Tintage must be the lady’s chosen lover. He remembered that he was the named heir.

Griff pulled his stool closer to Oriel’s bed, and fixed the end of his will more firmly to Oriel’s. Griff was not the man to be Earl. He did not wish it. He wished to serve Oriel, Earl Sutherland.

In the winter, in Beryl’s house, when they had first designed the scheme, Oriel had asked Griff if he would want to be the one to make the attempt. It had been asked in jest, but Griff knew that if he had said yes, Oriel would have stood behind him. Oriel had looked at him in the straight way he’d always had, bright eyes unafraid. “We have come too far and paid too dearly, to miss the chance,” Oriel said. “You could be the one to try it.”

“That I couldn’t do,” Griff had answered, and Beryl added, “Aye, and if you will rule, Oriel, then you must let people serve you. If you would govern, you must let them give you authority, even those who are also your friends.”

Now Griff looked at Oriel, bloody backed, and he remembered what Oriel had said, and what Beryl had said, and felt his will grip Oriel’s will tight, that Oriel might live to rule the land that had taken his heart. It was always so with Oriel. Even the mountains had seemed to him objects of wonder. To Griff they had seemed cold, and difficult underfoot, barren, colorless, death-dealing.

Griff sat, Oriel breathed, and Griff hoped of Beryl. He had no thought for any more than that: Oriel breathing, and hope of Beryl.

On the second day, Oriel died.

Beryl did not come.

Griff was alone.

And he must be Earl Sutherland.

After Griff had slept and bathed and shaved and dressed and eaten, after Oriel was buried beside the other Earls Sutherland, after many days, Wardel rode back to report that the puppeteer’s holding was uninhabited by any human creature, although the puppets hung in rows in their cupboards and the horse grazed in a fenced field. The news had no meaning.

After more days, they came to him, the contenders, Verilan and Garder, Lilos and Wardel. They treated him as if he were the Earl. They spoke of promises made to Oriel, and their intention to honor their word, and Oriel, in honoring Griff. Griff was still a guest at Lord Haldern’s house and there the old lords also came to him. Tseler told him he must first bend the knee to the King, in fealty, and then he must ride into the south, to bring his lands into order.

Griff had no lands. These were Oriel’s lands.

“My lord, you must,” Lilos said. The others echoed him, and “You must,” repeated Lord Haldern, Lord Karossy, Lord Tseler.

Perhaps he must, Griff thought, but that did not mean he would. He could find no words to speak to any of them.

When a boy knelt in the whipping box, the others ringed close around to watch. But for the boy it was as if they were far away, a distance across which their voices didn’t carry. For the boy in the whipping box, there was only the cut of the whip and the sharp stones on his knees and palms. He couldn’t hear or see anything else, except as you see things underwater, muffled and muted.

It was the Queen whose voice first spoke through to him. She came one day, and held out her hand to give him the beryl, with the falcon carved into its back. Griff wouldn’t reach out to take it. “Oriel said,” the Queen spoke, then stopped to weep, then spoke again. “He said that this stone should go to the Earl Sutherland, when he had the title. It is time, now, Griff.”

Griff shook his head, but she reached her hand up to hold his chin. He saw the fine lines near her eyes and mouth, and the grey in her hair, and the way a stiffness of the back hurt her; he saw the way the years had made marks on her beauty. He felt her little ringer where it touched the scar on his cheek. “Do you refuse him?”

Griff shook his head again and this time she allowed it. “I wouldn’t refuse him,” Griff said.

The Queen was satisfied.

“My lady?” Griff asked. The Queen would know as much as any man of the court, but she was not a man and so she could speak her knowledge when she chose. “What of the lady Merlis?”

Gwilliane turned away from him, and answered him as she looked out of a window, that he might not see her face and whatever it would reveal. “Merlis has placed herself at the traitor’s side. She now claims that they were wed in secret, during the summer. She has placed herself at the traitor’s side and must be taken, thus, for a traitor to her Earl. If she is a traitor to the Earl then she has forfeited her rights to the title and lands.”

So he need not marry Merlis. Griff could have done almost anything for Oriel, and he would be Earl Sutherland because Oriel asked it of him, but marry Merlis he could not. “Thank you, lady.”

She turned then, with a rustling of her dress, and he walked with her to the door, and he opened the door for her and he bent over her hand to place his lips on her fingers. “I wish you well, Earl Sutherland,” she said.

Four men waited in the hallway, three of them near Griff’s age and the fourth older by many summers. These four Griff welcomed. They had seen in Oriel what he himself had seen, and chosen to serve him. Griff gestured them into the room, asked them to be seated around the table, called out for a servant to bring wine and bread, sat down with them, and said what was in his heart. “I can be named Earl, myself, alone, but to be the Earl takes more understandings and skills than I have in myself, alone.”

They looked at one another, not understanding.

“I ask your assistance,” Griff said. “I’ve read the law,” he explained, “and the history, but I know nothing of how to set taxes, and assess for them. I have little experience of how to judge a man who speaks truly for the people from one who speaks for his own advantage. I know how to fight with sword and staff, but not with an army at my back. I have only the ideas Oriel and I spoke of to tell me how to shield a people from famine in drought or blight, how to plan against fair as well as foul weather, how to cull herds so that they can breed and feed in comfort. I think I know how to serve the King rightly and how to apply the law or change the law for greater justice, but of the rest—how to dress for occasions, who deserves what honors among the people of the court, how to train a servant, how to balance the powers of priests and lords and Majors, how to hold a Hearing Day, how . . . I know almost nothing.”

“I will serve you, as I can,” Lilos promised, “and so will all of my father’s house.”

“As will we all,” they said.

“I can lead soldiers for you,” Verilan promised, but “No,” Wardel argued, “the Earl must be known to lead his own men.” Verilan was quick to the quarrel, asking Wardel, “Do you think I would seek to reclaim what I have given over? Do you think I am so little to be trusted?” and Lilos was quick to defend Wardel, “You know that isn’t what he meant, so don’t pick a fight on that account.”

Garder spoke, then, with less heat than any of the other three. “The important thing may be as much what the Earl is seen to do, as what he actually does. If those who serve a man are true to him, as I think we are, there is no danger if Verilan leads Sutherland’s troops, as long as Griff rides at their head.”

“What about Verilan’s place in his father’s house?” Wardel asked. “For I am more easily spared, having more brothers, to go into the Earl’s close service.”

“Unless,” Lilos suggested, “there were two Captains over the soldiers, which would be less potential danger than one Captain, for one might grow greedy, or win the loyalty of soldiers and people, against his will. Two divide the dangers.”

“Ordinarily it is the brothers of the house who serve this purpose,” Garder said. “But if brothers are lacking, then there must be others, to be Captain, and to be steward, too.”

“But such men would have to give up their own inheritances,” Wardel pointed out.

Then, as if all had earlier agreed that this must be said, Wardel addressed Griff, “My lord Earl—No, Griff, you have to accept the title. My lord Earl, Tintage awaits your justice.”

Verilan spoke quickly. “To name the day and place of the hanging.”

“But he is a lord,” Garder pointed out unwillingly. “Yaegar might make the death of his son an excuse for armed rebellion.”

“But we saw how little Yaegar valued his son,” Lilos said.

“He dishonorably seduced the lady, too, if you ask my view,” Garder said. “Whether he wed her, as she claims, or whether he did not, he will have bedded her, you can count on that. To seal her heart to him, as bed pleasures can, and seal the Earldom.”

Griff covered his eyes with his hand, for Oriel had given the lady his heart.

“No one would deny Griff revenge,” Wardel said. “To kill an Earl is high treason, and an Earl’s sword can answer it. Surely Yaegar will deny the traitor?”

“He denied the son,” Lilos observed.

“But he did that for his own purposes,” Garder insisted. “I am uneasy in my mind about how to contain Yaegar. For he cannot resist the chance to bend another to his will, if he thinks he can profit of it. We should know more of what is in Yaegar’s mind, before anything is decided about Tintage.”

“But something must be done!” Verilan cried. “For Oriel was basely murdered.”

“And I think soon, before it has the chance to grow in people’s minds,” Lilos agreed.

They turned to Griff, who had been listening close. “Shall we hear him, then?” Griff asked. “I agree we can’t wait, but to condemn a man unheard—Even if there are witnesses to his deed, he can still be heard. Not just by the Earl, I think, and not just by Oriel’s companions, but by all, I think, for it is all he has offended in taking this life. Just as in taking any life, whether great or small, the murderer offends all who have given their freedoms over into the keeping of the law.” Griff tried to gather his thoughts together, for they were scattering like a flock of flushed birds. “I would ask the King and Queen, also, to hear Tintage. I would ask Beryl, could I find her.”

All but Wardel looked puzzled.

“Here they called her Baer, she was with us that first day, but—she is the puppeteer, the—she—” It was too many griefs at one time. “I would have the Queen and one or two of her ladies, if you know of ladies of good judgment, and good hearts, have you a sister, Lilos?” Griff didn’t know how to say what he was thinking of. In part, he cared about none of it and wished only to go away—to be perhaps a mountain man, living among ice and blinding light until he could die.

But he had to live and be Earl Sutherland.

“I would ask—I don’t know how many, but enough so that no one man’s enmity could condemn Tintage, and so that no one man’s friendship could save him. Can you find and bring them here?” he asked. “Your father, Garder,

and the Lords Haldern and Karossy, Verilan? The King, Wardel? and the Queen, too, and the best of the ladies, Lilos? Lady Rafella, too, she must be here. We gather at midday,” Griff said, and rose abruptly from the table.

The four, he thought, would take his abrupt rising and leaving as showing fixed purpose, as the proper action of an Earl. They wouldn’t know that grief had come down upon him unbearably, and he must be alone to put his arms around her, and feel her arms around him, to take enough comfort from grieving so that he could return to finish the business of the day. The business Oriel had given into his hands.

THERE WERE ALMOST TWENTY IN the great hall. Griff sat alone at the center of a long wooden table, and the rest were behind him, on benches and in chairs. Tintage faced Griff, and thus faced all. Two guards stood close beside him, and his hands were chained in front of him, and two more guards stood at each door, but Tintage didn’t look dangerous. He stood straight, as if unafraid, and calm, but his eyes, like moles wandering above ground, shone fearful, and he considered his words carefully before he spoke.

He bowed his head to the King and the Queen, to the other lords and ladies present. He greeted Rafella not by name but by title; not, however, by her title as Lord Haldem’s wife, but by her title in relation to himself. “I am glad to see you, Aunt,” Tintage said.

At the last, his mole eyes met Griff’s.

Griff had fallen into flames. His heart choked him and he could see only Tintage, and he had a sword near his hand—

“My lord,” Lilos asked. “Are you unwell?”

Verilan spoke softly. “Let him do it. Who better?”

Griff shook his head, to clear it. For blood called out for blood, when lands and wealth were at issue. If Griff revenged Oriel now, who might revenge Tintage?

He pushed himself back into his chair and gripped its carved wooden arms. He forced himself to look at Tintage—why was the man smiling now? Oriel would have slit the man’s throat, if it had been Oriel now in the Earl’s chair and Griff buried underground with his stiff fingers wrapped around the hilt of his sword. When the avalanche rolled down toward Rulgh, there had been joy in Oriel’s face, as well as long hatred and stern necessity.

The Runner

The Runner By Any Name

By Any Name Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do?

Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do? Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things: Mister Max 1

Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things: Mister Max 1 The Wings of a Falcon

The Wings of a Falcon Bad Girls in Love

Bad Girls in Love Toaff's Way

Toaff's Way Building Blocks

Building Blocks Orfe

Orfe Tell Me if the Lovers Are Losers

Tell Me if the Lovers Are Losers It's Not Easy Being Bad

It's Not Easy Being Bad The Book of Kings

The Book of Kings Dicey's Song

Dicey's Song A Solitary Blue

A Solitary Blue Tree by Leaf

Tree by Leaf Sons From Afar

Sons From Afar Teddy & Co.

Teddy & Co. Jackaroo

Jackaroo Elske

Elske Izzy, Willy-Nilly

Izzy, Willy-Nilly Come a Stranger

Come a Stranger Mister Max: The Book of Secrets: Mister Max 2

Mister Max: The Book of Secrets: Mister Max 2 Seventeen Against the Dealer

Seventeen Against the Dealer The Callender Papers

The Callender Papers The Vandemark Mummy

The Vandemark Mummy Tale of Birle

Tale of Birle Glass Mountain

Glass Mountain The Tale of Oriel

The Tale of Oriel The Book of Lost Things

The Book of Lost Things The Book of Secrets

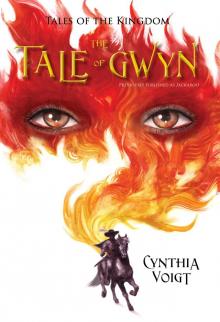

The Book of Secrets Tale of Gwyn

Tale of Gwyn