- Home

- Cynthia Voigt

Glass Mountain Page 5

Glass Mountain Read online

Page 5

8

What the Machine Said

I was unloading grocery bags—cleaning supplies for the crew of four who came every two weeks to take care of floors and windows; a few bottles of wine; green shrimp for a scampi—listening to the phone messages.

Beep. “Mr. Wilkerson at Sulka’s calling. The suits Mr. Mondleigh ordered are ready to be picked up.” Beep. Whirr.

I checked the time; I could fetch them that day, if I hurried.

Beep. “You are adorable, Mr. Bear,” the familiar voice, low and rough-edged, like a cat’s purr. “Absolutely adorable. Even a non-Irish girl loves emeralds. I know it’s a couple of days early, but I could make a pitcher of green beer—if you wanted. I’ll be here all afternoon, in case you felt like calling. I’ve got no plans for tonight. So if you’d like to do something? I’m available.” Beep. Whirr.

My instructions were not to call Mr. Theo at the office except in case of emergency; this was no emergency message, although the voice, vibrating, implied a certain urgency. I grinned, and laid a bottle into the wine rack.

Beep. “Theodore Mondleigh. You don’t know me. My name is Rothman, Howard Rothman. From Minneapolis. I have a software company that does business with Hal Patricks. Hal gave me your number, and from what he says I’m interested in talking to you. I’ll be in town Monday; I’m booked into the Hilton all week. It sounds like we both might make some money, so give me a call and we’ll set something up. It’s Friday, eleven fifteen my time.” Beep. Whirr.

Again, I checked the time, picturing the sun making its arced way over a map of the United States to figure out whether I should be adding or subtracting an hour, then gave myself a mental shake: what did the time matter? Why was I so concerned with the time?

Beep. “Theo? Your father wants you here in time for lunch tomorrow…something about papers he wants you and Davy to look at. That’s the first thing. Do you remember, we’re having dinner with the Rawlings? Be sure to pack something appropriate. They’re more…formal than we are. Oh, and Davy said he’d like a game of squash Sunday morning. I’ll book a court. There was one more thing…but I can’t remember. I hope it wasn’t important.” Beep.

Distracted by hopefulness: that explained me to myself. I was counting days until…

Whirr. Beep. “Teddy? If you can’t make it Saturday, how about Tuesday for dinner? It’s been too long, much too long. You’ll love hearing about my new job—it’s a giggle, I promise. But you’ve been hard to get ahold of for the last two or three weekends. What’s going on? Anything interesting? Oh, it’s Muffy.” Beep. Whirr.

I remembered Muffy. Muffy was fluffy, that was why I remembered her. Mr. Theo’s affiliation might have been Episcopalian, but his tastes were Catholic.

Beep. “Theo? I remembered, your father wants a general outline of your will. He’s rewriting his. I hope…you don’t mind?” Beep. Whirr.

Well, hope springs eternal.

Beep. “Gregor? I won’t be in for dinner. Don’t wait up.” Beep, beep, beep.

Which meant that he didn’t plan to be home that night. I looked at the mound of raw shrimp—more than I could eat on my own. A De Jonghe certainly wouldn’t freeze, but with the shells still on, although not as tender as fresh, still, in a shallot-tomato sauce, over a pasta…It is the lack of waste I admire most in French kitchens. If you live in New York, you have to know how close we are to being buried by our own garbage, and you may even think it serves us right.

I thought I could get the shrimp wrapped and into the freezer before I headed over to Sulka’s, and double-checked the time.

9

Improvisations on a Theme

While I waited to know if she would risk a third meeting, Mr. Theo accelerated his social life, which kept me busy and I was not ungrateful. Ten days pass quickly when your skills are being challenged. This period began with a standing rib roast on an evening of gusty, dark March rains.

I opened the door to Mr. Theo and saw that he had a woman with him. Behind them, the limousine drove off. I took his umbrella, their raincoats, and her rain hat. She was an ash blonde, blue-eyed, with a rangy golfer’s build. He greeted me formally. “Good evening, Gregor.”

“Good evening, sir.”

“Will dinner stretch to one more? We don’t want to go out again, do you?”

“Not likely,” she said. “Not in this weather.”

“There’s a roast for dinner,” I told him. “More than enough.”

“Good. Let’s have a drink. How does that sound to you, Holly?”

“Absolutely great. It sounds absolutely perfect.”

He put a hand on the small of her back to guide her into the library. I hung up their rainwear, made the necessary alterations to the table, and opened a bottle of burgundy to accompany the standing rib roast.

Beef Stroganoff, its sour-creamy gravy shot through with fresh dill, was what I served the next night to Mr. Theo and a redhead. Molly, I named her, after Sweet Molly Malone, because of her easy laugh and her large, strong-looking hands. For breakfast she wanted juice, fresh-squeezed if I could manage that, and eggs, and scrapple if I had any but bacon would do, and toast, and fried potatoes if that was all right.

Cold beef in thin slices—the day was unseasonably warm—is what I set down before Mr. Theo and a curly-haired brunette I called Dolly, for her Kewpie mouth. Folly ate roast beef hash with a flash of rings—wedding ring, engagement ring, and the odd blockbuster sapphire—and gave me an occasional predatory glance as if to say that when she had finished with Mr. Theo…Polly, with her long honey-blonde hair and visible gladness, ate shepherd’s pie and talked about how incredibly lucky she was to have gotten the job she held, the apartment she shared with a cousin, an evening with Mr. Theo all to herself.

The beef went quickly. Turkey—tetrazzini, hash, capilotade, curry—lasted no longer. Time flies when you are working hard.

On the Saturday morning before the Sunday afternoon I was waiting for, a recently shaven Mr. Theo sat at the kitchen table, drinking his morning tomato juice, looking altogether fresh and pink and pleased. I had a pan of bacon frying.

“Will the young lady want breakfast?”

“I took the young lady home a few hours ago. Some young ladies, Gregor, feel compromised if they stay the night.”

“And how would you like your eggs?”

“Scrambled, I think. Yes, scrambled.”

“We have finished with the turkey, sir. Should I procure a leg of lamb?”

“Do I detect a note of disapproval?”

He wasn’t really inquiring. I didn’t really answer. I whisked eggs. “If anything, a note of admiration.”

Mr. Theo laughed, but I didn’t turn around. “You’re pure gold, Gregor. I have an impulse to give you a raise, but that would be the action of a man who felt guilty. And I don’t.”

“I don’t need a raise.”

“But you’re right about me. I don’t know what’s gotten into me. Which isn’t to say I’m not having a fine time, because I am, I’m having a fine old time. And it’s not as if I’m not taking reasonable precautions…”

“I’m glad to hear that, sir. This is no time to be cavalier about sexually transmitted diseases.”

“You can say that again,” he said. I didn’t. “You know what I think? I think it’s the idea of marriage. That, and all the family weekends out at the Farm, it makes me…horny? No, incredibly randy, that’s what it is. I can’t pass anyone by, I can’t say no to anyone. I’m not saying it’s not fun, but—Does this make any sense to you?”

“Will you be getting married then?” I transferred the eggs to a plate and laid strips of bacon beside them. I added buttered toast to the plate.

“Good God, no. The parents are putting on the pressure, but I hold firm. All very civilized, of course, nothing actually stated, just family get-togethers—as if the Rawlings were their best friends or long-lost cousins or something. I don’t know what poor Pruny makes of it, although she doesn’t seem to care wh

at goes on around her. I never know what she thinks. But I tell you what, Gregor. It’ll be a relief when the parents go off on vacation next week. Four weeks of peace, and privacy.” He munched on a slice of toast. “I don’t know what time tomorrow I’ll be able to get away. There’s always a big lunch on Sunday.”

“I’ll leave something cold for you, shall I?”

“Gregor?” He looked up from his breakfast. “What do you do on your days off? I suppose you must have a private life?”

I wasn’t going to tell him, and he didn’t want to know. Instead I asked, “Isn’t that the proper order of things? I’m supposed to know everything about you, and you’re supposed to know nothing about me.”

“I know you’re probably better educated than I am,” Mr. Theo agreed, “and we both know you’ve got better taste.”

“That also is the proper order of things, isn’t it?”

“You are a cynic.”

“I’m afraid not, sir.”

10

A Golden Flute

We had left the church together, left the concert together, and stood together on the steps where earlier I had waited for her. She wore a kilt and walking shoes and a down vest, looking like the many other women there who had hurried in from the country to hear Rampal play a benefit for African refugees. I was still dazed by the memory of the bobbing figure, and the notes as golden as his flute moving through the church like sunlight through leaves. She had sat with what I was beginning to recognize as a typical attentive stillness. Now we stood in the last of the late-afternoon sunlight. I could hear remembered music more clearly than the sounds of city life around us. I put my thought into words. “Wonderful.”

“Unmn,” she answered, then changed the topic. “You listen with your shoulders.”

“What?”

“Your shoulders…move. With the music. Maybe your neck too, chin. It’s not unseemly. You’re never unseemly,” she teased me.

I came back to the real world and wondered if this was the moment for the next step.

“I’m always saying thank you,” she said, holding out her hand for me to shake.

I didn’t take it. “And walking away.”

“Yes.” She put both hands into the waist-high pockets. “I don’t know what James thinks.”

“James?”

“Our butler. He calls you the Gentleman. ‘The Gentleman left this for you, miss.’” It was a fair imitation of his voice, redolent with nasal dignity, and I laughed.

“Does it matter what James thinks?” I asked.

“No.”

“What do you think?”

“I don’t know what to think. So I don’t. I enjoy your company, and the things you ask me to do.”

“Am I good enough company to take you to dinner?” It was time to try, to at least try.

“I can’t,” she said quickly.

“I’ll walk you home though. It’s all right, I already know where you live. I won’t go to the door, just stand on the corner until you’re inside. See you safely home.”

She considered that, then nodded her head, agreeing to it. “You’re old-fashioned, aren’t you?”

“I’m afraid maybe I am.”

11

What the Machine Said

I had purchased a spring bouquet, on impulse—little irises, a few tulips, daffodils—and trimmed their stalks under running water. While I was arranging them in a clear glass vase I listened to the few messages on the answering machine. Once the flowers were displayed, I’d think about where to put them.

Beep. “Theo? It’s Mother. To remind you about tomorrow, the opera. We’ll meet you at the box. You two might…have dinner, before.” Beep, whirr.

Beep. “Lisette here. Any man I don’t hear from for five weeks I’m finished with. The men I respect at least call up, to say it’s over. That’s the way I like it. That’s the only way I take it. Good-bye, Teddy Mondleigh.”

Beep, whirr, beep. “Mr. Bear, I haven’t seen you for eight days. And I miss you, I honestly do. Are you gonna call me up or anything? Is something wrong, did I do something wrong?” Beep.

Whirr, beep. “Hi, Teddy, it’s Bonnie, and thank you for the dinner and everything. Any time you’d like to do it again, you know where to find me.” Beep, beep, beep.

The flowers I put on the kitchen table, where they shone bright against the gray window. The flowers—I hadn’t understood it—were for me.

12

A Night at the Opera

I could have envied Mr. Theo his dressing room. Paneled in golden oak, it was an affair of closets—closets to hold hanging clothes, closets fronting for caned drawers, and one closet that opened into a floor-length three-way tailor’s mirror. Recessed lighting and the thick brown carpet soft under a bare foot…Enviable.

Ordinarily I was only responsible to care for Mr. Theo’s wardrobe, but when he had a black-tie occasion, I played valet. It wasn’t that he couldn’t put in his own studs, tie his own tie, slip his own feet into the patent-leather shoes; he simply preferred me to hold ready the parts of his ensemble, one after the other, and pass them to him at the proper time. I didn’t fault him. We were playing out a scene; the mirrors reflected us, man and manservant. Mr. Theo had said as much to me, one of the first times I valeted him that way. “I feel like royalty.”

Looking at our reflections, I had remarked, “Royalty, or a woman. Women must feel that way.” The air between us had become immediately tense, charged.

“You’re not gay, are you, Gregor?” If I had been, and wanted to keep the job, I’d have denied it; as it was I simply denied it. “Bisexual?”

“No.”

He wanted to ask more, the next logical step, but didn’t quite dare. What, I had wondered, looking at his reflections, would his reaction be if I asked him the same set of questions.

That evening, as I held out the starched dress shirt, Mr. Theo remarked, “Many gentlemen wear turtlenecks with their tuxes.” He worked the studs up the front of his shirt.

“I’m sure many gentlemen do.” I dropped the next stud into his hand.

“Stuffy, Gregor, you sound awfully stuffy.”

“Yes, sir.”

“What you’re hinting is that the kind of gentleman I am wouldn’t do that.”

“It’s the more artistic, more bohemian style of gentleman who will wear a turtleneck. It’s the theatrical style of gentleman who has ruffles, or a pastel shirt.” I put the link through the French cuffs on his right wrist, then moved behind him to do the left.

“You mean the crass style, don’t you? Or gay—gays go in for color and ruffles. But I forgot, you don’t like that word.”

I passed him his trousers. “It’s cost us at the least one good line of poetry.”

He stepped into the pants, pulled them up, zipped and buttoned them. “Don’t be too stuffy, Gregor.”

“As you wish, sir.”

His reflection grinned at me. I passed him the cummerbund, black of course.

“Do you know anything about this opera? Marriage of Figaro? It’s Mozart, right? I’m not a complete dunce, I know that much.”

I put his evening shoes down by his feet.

“Is there something interesting I could say about it, so I don’t come across as a complete jerk? Pruny has cultural interests—” He ran a little finger along a mocking eyebrow. “I don’t want to give her false hope, but I do have my pride. Do you know anything about it?”

“There’s the point of the connotations in the title.”

He waited for me to go on. I held the tie ready. He turned his back to the mirror and I put the tie behind his neck. “Well?” he asked. “Are you going to tell me?”

“The title in Italian, Le Nozze di Figaro…” I gave each syllable Italianate values, apple-plump vowels, a savoring of the double z and an embellishment of the r.

He tried to do the same, a pale imitation.

“Nozze,” I told him, “isn’t only the nuptials, the marriage ceremony, it’s…the wedding

night, something like that, and it’s plural, whatever you want to make of that.”

“And?” He was impatient now. “What do I make out of that? A wedding night only matters that way if everyone’s a virgin—no, if the girl is. Which sounds pretty chancy as a conversation piece, virginity. Pruny’d probably faint. Or blush. Or something.”

“There’s the pastoral tradition,” I offered, stepping back to be sure that the tie was perfectly even.

Mr. Theo groaned. “Do you mean there are going to be shepherds and shepherdesses doddling around on the stage?” I laughed. “I don’t think I can take that,” he said, and seemed sincere.

“Pastoral more in the music than the drama,” I promised him. We were grinning at one another in the mirror. “You could talk about the role of women.”

“Now that sounds more like it. You don’t have to know anything to talk about that. You just say something like”—he slipped his arms into the jacket—“‘Interesting what he does with the role of women in the world of the play.’ I remember that trick from freshman English; I can do that. You sound smart without having to actually know anything. Don’t look at me like that, Gregor. I know my limits.”

He studied himself in the mirror. I turned to take the dress overcoat from its hanger.

“I should take you with me to a business lunch someday, let you see me in my element, teach you a little respect and admiration.”

It wasn’t an invitation. If it had been, I would have declined it.

“Do you want me to drive tonight?”

“Why should both of us be bored?” He looked at his watch. “The garage said they’d have the car here by seven thirty; it’s about time. You know, if we were identical, I could send you in my place. You’d probably enjoy it.”

The Runner

The Runner By Any Name

By Any Name Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do?

Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do? Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things: Mister Max 1

Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things: Mister Max 1 The Wings of a Falcon

The Wings of a Falcon Bad Girls in Love

Bad Girls in Love Toaff's Way

Toaff's Way Building Blocks

Building Blocks Orfe

Orfe Tell Me if the Lovers Are Losers

Tell Me if the Lovers Are Losers It's Not Easy Being Bad

It's Not Easy Being Bad The Book of Kings

The Book of Kings Dicey's Song

Dicey's Song A Solitary Blue

A Solitary Blue Tree by Leaf

Tree by Leaf Sons From Afar

Sons From Afar Teddy & Co.

Teddy & Co. Jackaroo

Jackaroo Elske

Elske Izzy, Willy-Nilly

Izzy, Willy-Nilly Come a Stranger

Come a Stranger Mister Max: The Book of Secrets: Mister Max 2

Mister Max: The Book of Secrets: Mister Max 2 Seventeen Against the Dealer

Seventeen Against the Dealer The Callender Papers

The Callender Papers The Vandemark Mummy

The Vandemark Mummy Tale of Birle

Tale of Birle Glass Mountain

Glass Mountain The Tale of Oriel

The Tale of Oriel The Book of Lost Things

The Book of Lost Things The Book of Secrets

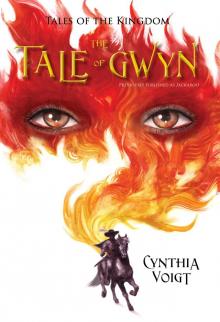

The Book of Secrets Tale of Gwyn

Tale of Gwyn