- Home

- Cynthia Voigt

The Callender Papers Page 8

The Callender Papers Read online

Page 8

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I’ve woken you. I don’t know what—” But I did know what.

“Tell us what it was you dreamed,” Mrs. Bywall said. She looked quickly at Mr. Thiel, as if she might have spoken out of turn.

“I can’t,” I said.

“She was sobbing,” Mr. Thiel reported to Mrs. Bywall, “and calling out.”

“For Miss Wainwright,” Mrs. Bywall said, nodding her head.

“No,” he said shortly. “Do you often have nightmares?” he asked me. “You don’t seem the type.”

“Not since I was small,” I told him. “Neither do I scream,” I added. But somehow, remembering that, I felt an unbidden urge to smile. “I apologize for screaming at you.”

“I choose to forget that,” he said, but his dark eyes remembered.

“It was loud enough,” Mrs. Bywall said brightly, with another glance at Mr. Thiel. “If we lived close to other people, we’d have everybody in here. It raised me up in my bed like a popover in the oven. I was that surprised.” She kept looking over at my employer, as if asking permission to utter the next sentence. “You’ve got a good scream, Jean, loud and healthy.”

At her practicality, I did smile openly, struck by the humor of what she was saying. Gradually, the ordinariness of the room entered my spirit. That sounds odd, but that’s just what it felt like. It was as if the familiarity of the room, of the people sitting in it with me, sipping foamy milk, as if the everyday quality of it swept the fears of my dream out of my memory. Mrs. Bywall still looked half asleep, but she talked on. I began to understand who it was she was afraid of, who it was that caused her to check and consider what she said. I began also, I thought, to glimpse the woman she really was behind her impassive face. I ignored Mr. Thiel and gave her my full attention.

“Don’t I know about dreams,” she said. “I had nightmares myself, before going to prison. Then, when once I was there, do you know what I dreamed of? Marlborough and my family. I had happy dreams then. I’d dream it was a birthday, when I was a child. Once I dreamed that Charlie, my Charlie, you know, came and carried me away, rescued me. I guess I never wanted to wake up from that dream.”

“I don’t dream now,” Mr. Thiel said, entering into the conversation. “I used to. Now I paint. It may be much the same thing,” he said. All during this time he watched my face closely. What did he suspect me of, I wondered; why should he watch me so closely?

“It’s what you don’t think of during the day that comes creeping out of your mind at night, that’s what makes dreams,” Mrs. Bywall said. “I can’t put proper words to it, but that’s what I mean.”

I agreed with her theory of dreams, but did not say so. Instead I said, “It must be the middle of the night.”

“Nearly so,” Mr. Thiel agreed. “The wind has died down, the rain has stopped. And you have bare feet. If your aunt could see you now, she’d probably give me the rough side of her tongue.”

“Yours are bare too, aren’t they?” I pointed out. I looked under the table. They were.

“I’m a grown man,” he told me. “I’m allowed to catch my death of cold, whenever I want to. Can you sleep now?”

“I think so,” I said. I remembered my manners. “Thank you for waking me.”

He shrugged, as if to say that didn’t matter. I returned to my room, turned down the lamp and lay quiet in the darkness. They remained downstairs. The dream did not return. Instead I found myself wondering: for whom did I call out, if not for Aunt Constance? I fell into a deep sleep before I had begun to think of an answer.

The next morning, before I started to work, I spent some time thinking carefully. I stood at one of the library windows, looking out toward the stream, over lushly grown trees. The sun was bright. The world glistened. Leaves shone in the sunlight. It was a cheerful view.

The view inside my imagination was not at all cheerful. It was gloomy and muddled, filled with vague ideas and fears. I kept my eyes on the clear world outside and thought carefully, as I had been taught.

First, my own feelings. I was, of course, embarrassed at the commotion I had caused the night before. Mr. Thiel and Mrs. Bywall had been extremely kind to me. I appreciated that, but was still embarrassed. And I understood well what Mrs. Bywall meant about things creeping out in dreams.

To learn of those deaths, those mysteries, even though they were now ten years old, frightened me. Remember, I had spent all my life under the guidance of Aunt Constance. My years, my days themselves, had been safe, secure, orderly. I knew what would come in the seasons, in the hours. Aunt Constance’s patience and kindness guided me. Now, unexpectedly, I had come into a place where such deeds of darkness happened. Worse, they might have been committed by the people among whom I was living. It was as if you went to sleep in your own bed and awoke to find that same bed afloat in an endless sea, with sharks swimming about. Nothing was sure any more.

I felt that the world itself had changed and that it would never be steady under my feet again. I felt I understood nothing of people and had no way to learn. I felt fear.

Until you have felt fear, you cannot imagine it. Once you have really felt it, you know that all your earlier nervousness was but a pale shadow. Fear that morning hung off the bottom of my heart, like a monkey with a devil’s face. Its four strong hands clung at my heart, pulling down with its weight, and its hairy countenance grinned diabolically up at me with wise, dark eyes. I knew I had to look at the creature. I forced myself to do so.

I thought carefully: I could trust those who were not involved. I could trust Aunt Constance. I could probably trust Mac. But what of those among whom I was living? What of Mr. Thiel? What of Mrs. Bywall? And the Calldenders, down the hill? All of those people were somehow concerned in this.

Aunt Constance had allowed me to come here. But could she not be deceived by this man who was so generous to her school? Whom she saw only once or twice a year? Who could so easily mislead her, by his interest—however ironic—in her ideas?

What did it all have to do with me? Why should I feel this unreasonable fear?

What had Mr. Thiel been doing in my room? Had he really heard me calling? What had he heard that brought him from his room in bare feet?

That was not careful thinking, I knew. So I started again, reassuring myself by remembering that all this had occurred ten years ago and had nothing to do with me. The death of Josiah Callender came first. Then the death of Irene Callender, Mrs. Thiel. There was the disappearance of the child and of the nurse. Those two were close together in time and probably were connected. So far, it made sense. What was the key?

Added fact: Old Mr. Callender’s heart had failed him when his daughter had been brought into the house, when she had been found; although it had not failed him when she had been missing. (All of the Callenders had searched the night through, as well as Mr. Thiel.) So that old Mr. Callender must also somehow be concerned.

Arranging it in this way, like a geometry problem to be solved, eased my spirits. The answer would lie back, ten years or more, in time.

Then something struck me that should perhaps have been obvious before. There might be a clue, or the answer itself, in these boxes of papers. I thought carefully, although my imagination wanted to rush ahead. The Callenders seemed ordinary people, wealthy it was true, but even so just people, with the usual problems and quarrels, purposes and confusions. It was not usual for ordinary people to die in such fashion or to disappear. Something must have occurred those many years ago to change everything, to make these ordinary people subject to such unreasonable events.

That, also, made sense. I was an outsider, and so could not know what had happened. Mac knew, I thought, no more than he had told me, so that I could assume that the villagers also knew no more. Only the Callenders knew, and Mr. Thiel; and perhaps it was this of which Mrs. Bywall was so careful not to speak. As an outsider, I could bring no private information to the case. But I had before me seven boxes of papers, where the truth might be hidden. If so

, it would most likely be in that last, half-filled box. Carefully, if I were to continue through the papers with this object in mind, I might notice something, something I would overlook in the ordinary course of things. I had organized my approach to the work, and what I was doing now was primarily tedious, just reading closely and sorting. I knew by now what to expect, so that I could work more quickly, less carefully. I could hurry through those intervening years.

I returned to the papers on the table, satisfied that I was doing all I could. Unbidden, I remembered those two tombstones and noticed something curious about Irene’s. “Beloved wife of Daniel Thiel,” it said, then “beloved mother.”

I wondered who had ordered those tombstones, who had caused that odd and incomplete inscription. That information, too, might be among these papers.

At luncheon that day, Mr. Thiel asked me if I would like to accompany him to the village. I said I would not. I wanted to get back to the library, now that I knew what I was looking for. I felt hurried, as if there was some urgency to find out in time. Then, I also wanted to go back to the falls that afternoon, to see the place again as I had first seen it, to lay the ghosts of my dream.

“Have you no letter to mail?” he asked sternly. I remembered the short note I had written before going to bed the evening before. He said he would mail it for me. “Your aunt,” he said, “will be concerned.”

“I’ll address the envelope immediately after lunch,” I said. “You are kind to mail it for me.”

“Mrs. Bywall and I take our responsibility for you quite seriously,” he answered.

“I hadn’t thought of it like that,” I said, answering as tonelessly as he. “Aunt Constance believes in accepting responsibility. She makes her students be responsible to her, as well as making herself responsible for them.”

“Perhaps that is one reason why her school is so successful,” Mr. Thiel remarked.

“Is it successful?” I asked. I had never heard an outsider’s view of Wainwright Academy. I had heard the usual complaints and gratitude, from the girls and their parents. I had noticed that everyone respected Aunt Constance.

“Don’t you know? I would think you’d know that. It has the reputation, which it deserves, of giving the best education to young ladies in the Boston area. It has also the reputation of producing suffragettes, because it doesn’t confine its curriculum to fine arts and domestic arts. For families who want their daughters to be educated as their sons are, it is the one place to send a female child.”

“Really?” If he had meant to please me, he had succeeded.

“Really. Your aunt is a remarkable woman.”

“I knew that,” I said. “I just didn’t know this. It makes me more proud of her.”

He seemed willing to continue the conversation. “When I first met her the school was quite young,” he said. “She has worked hard and well.”

“That was before I came to her,” I said carefully. When exactly had he met Aunt Constance, I wondered; how well did she know him?

“Oh yes, I remember,” he said. As he did so, his eyes became glad, as if he had been a different kind of man in the past. “Your aunt had long been a friend of my wife’s.” I just nodded my head. “She was an imposing woman, your aunt. I was quite frightened when I first met her.”

In my surprise I forgot that I was searching for information, and I entered into the conversation without thinking. “You were frightened?”

“Irene admired her. So I badly wanted her to approve of me. I was younger then.” He smiled at my obvious disbelief. “And then, too, your aunt is such an imposing woman, so strong in her opinions, so clever in her arguments—she overwhelmed me. At first,” he added, “and not for so very long, after all. She seemed to like me. Not everybody does, as you have pointed out to me,” he said. “I felt sure she would be a success.”

“Yes, she gives you that confidence,” I agreed.

“Besides that, she introduced me to the art dealer in Boston who handles the sales of my pictures. Like many others, I am grateful to your Aunt Constance.”

“I will write her more frequently,” I said.

“You are very like her,” Mr. Thiel said. Before I could answer, he excused himself from the table, as if he were made uncomfortable by paying me a compliment. As soon as he had left the room, my suspicions resurfaced: why should he take the trouble to make himself agreeable to me? Unless—because the papers had been in his care all these years—he knew more of what was in the boxes than he had admitted to Aunt Constance. Unless he realized that his unfriendliness might cause me to leave the house and leave the job unfinished. But why should he care about that, unless he intended me to find something he already knew was there in the boxes? or, I thought carefully, slowly, he wanted to see if I would find something that was there to be found, unless he wanted to test the effectiveness of its concealment.

I worked for another hour after luncheon, finding nothing of interest to my particular problem. I heard Mr. Thiel leave the house. Later, I changed into my new dress and set off with bare feet to the falls. I carried a book with me, as if I planned to read. When I got there I put the book down under a tree and stood silent, to hear the sounds, to examine my own feelings. The terror the place had held in my dreams was gone. I saw that the stream was still running fast from the rains, and I approached the edge of the ravine with caution, remembering Mac’s care of the day before. I lay on my stomach and looked down into the pool.

She had lain there, helpless. If you fell down the sides of the ravine, either the undergrowth or the boulders would break your fall, I thought. The sides were steep, but not sheer. The drop down, rolling as a body would, would not end at the pool of water.

If, however, you fell somehow from the falls themselves, if you were carried over the steep cliff there and tumbled down, then you would probably have broken bones. You might well be knocked unconscious.

If someone strong held you, standing where I lay, and hurled you out over the edge, down the ravine, then too you might be too injured to pull yourself out of the water.

It was just when my thoughts had reached that point that someone touched my shoulders, two strong hands. I gasped. I clutched at the ground. I tried to bury my head in the grass.

“Jean. It’s only me!” Mac’s voice said.

I sat up. “It is I,” I said. “It must be nominative.”

Mac looked amused. “I didn’t mean to scare you.”

“Where were you? Why didn’t you call out that you were coming?”

“I thought you’d seen me. I’ve been here all along.”

That was even worse.

“You were looking right at me,” he protested, seeing the expression on my face. I had to believe him: his eyes were surely sincere.

“I didn’t see you,” I admitted.

He grinned. “You were so quiet lying here. I got worried.”

“She must have either gone over the falls,” I said slowly, “or have been thrown into the water.”

“That’s what I’ve thought,” he said. “Unless—” he stopped.

“Unless what?” I asked.

“I don’t know if I should be telling you all these things,” he said. “My father got pretty mad at me last night. I told him we’d come up here. I told him I’d told you about Mr. Thiel and the nurse and all. You see,” he apologized, “I’d promised him not to gossip, and so I had to tell him. But it wasn’t gossiping, was it?”

“What did he say?”

“He said he thought I’d shown poor judgment. He said you were young—”

“I’m not much younger than you,” I protested.

“And a girl—”

“What difference does that make!”

“He said a lot more. And then he asked me what I thought you would think of Mr. Thiel.”

I could not answer that.

“He was really angry,” Mac said. “And he’s right.”

“But it’s too late, isn’t it?” I argued. “You’ve

already told me. So you might as well tell me the rest, hadn’t you?”

“I don’t know,” Mac said. He pulled at the grass.

“Fear comes from ignorance,” I said, echoing Aunt Constance. “If you’re worried about frightening me, you’ve already done that.”

“Father said that.”

“And all we can do now is try to figure out what happened.”

“Could we?” he asked. He looked eager. “Do you think we really could?”

“So you have to tell me. Whatever it was you thought that you weren’t going to.” My grammar was atrocious, but Mac understood me.

“I thought that if she had been injured somewhere else, then somebody might have brought her body up here. Maybe thinking she was dead or something.”

“He’d have to be strong,” I said.

“So would anyone who threw her over the edge. Otherwise,” he said, “it doesn’t make sense, does it? The bank is steep here, but not that steep.”

I agreed with him.

“What I can’t figure out is why,” I said. “I mean, why in the first place. What difference would her death make?”

“It could have been an accident,” Mac said. “That’s what the jury decided it was.”

“But people don’t think so,” I argued, “and you don’t think so, and Aunt Constance didn’t say so. There is something wrong.”

“There was a lot of money,” Mac said. “Maybe somebody wanted the money?”

“It was her fathers,” I said, “and he was still alive.”

“It’s the nurse and the child,” Mac said. “That’s what makes it so very mysterious. That’s what convinces me there was something wrong.”

“Something dangerous.”

“Something evil, I think.”

For a minute I was afraid I would cry. “I don’t know anything about evil,” I said, feeling the helplessness I had felt in my dream take over again.

“I know some boys who would rather cheat on an exam than study for it. I know one who likes to make little kids cry, a bully. He wants them to be afraid.”

The Runner

The Runner By Any Name

By Any Name Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do?

Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do? Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things: Mister Max 1

Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things: Mister Max 1 The Wings of a Falcon

The Wings of a Falcon Bad Girls in Love

Bad Girls in Love Toaff's Way

Toaff's Way Building Blocks

Building Blocks Orfe

Orfe Tell Me if the Lovers Are Losers

Tell Me if the Lovers Are Losers It's Not Easy Being Bad

It's Not Easy Being Bad The Book of Kings

The Book of Kings Dicey's Song

Dicey's Song A Solitary Blue

A Solitary Blue Tree by Leaf

Tree by Leaf Sons From Afar

Sons From Afar Teddy & Co.

Teddy & Co. Jackaroo

Jackaroo Elske

Elske Izzy, Willy-Nilly

Izzy, Willy-Nilly Come a Stranger

Come a Stranger Mister Max: The Book of Secrets: Mister Max 2

Mister Max: The Book of Secrets: Mister Max 2 Seventeen Against the Dealer

Seventeen Against the Dealer The Callender Papers

The Callender Papers The Vandemark Mummy

The Vandemark Mummy Tale of Birle

Tale of Birle Glass Mountain

Glass Mountain The Tale of Oriel

The Tale of Oriel The Book of Lost Things

The Book of Lost Things The Book of Secrets

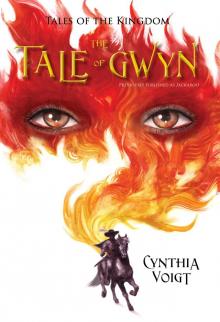

The Book of Secrets Tale of Gwyn

Tale of Gwyn