- Home

- Cynthia Voigt

The Wings of a Falcon Page 8

The Wings of a Falcon Read online

Page 8

Oriel was about to offer her the fish in exchange for food, when she wheeled away. “Almost men, almost full-grown, especially the brown one. Not babies. But what are they thinking of?” She wheeled towards them and jabbed with a pointing finger. “What are the men of Selby thinking of when they send you?”

“Nobody sent us,” Oriel said.

“Then how would you know where to find me?”

“We didn’t.”

“Liar,” she mumbled, then answered herself, “and how could a lad not be a liar? The world the way it is.”

“Truly, Granny,” he said, having recalled the proper address for the old women in the market town. “Why should anyone send us? We came hoping to trade fish for bread, if you have it.”

“Because if I don’t eat I’ll die, so they send me food. Bread, fish, cheese, onions, turnips. It waits on the stoop, mornings. I’m never left to go hungry. Because if I die they don’t know what worse will happen to them. They’re afraid. That’s why I have this cottage,” she said, nodding her head, tapping at the side of her head with a crooked forefinger. “They drove me out of Selby, the men of Selby, and they keep me here. Sit down. As long as you’re here. You’re safe enough with me. I’ve built no fire, and the shutters hide my light. Should the soldiers come, I know a safe place.” She seated herself on the solitary stool.

“We wish to trade our fish for bread,” Oriel said.

She didn’t seem to be looking at them; or, if she was looking at them she didn’t seem to be seeing them. “There’s the bed,” she said. “There’s the floor.”

A stool, a small square table, the bed—and the room was crowded. “Have you bread, Granny?” Oriel asked again.

“Not for days. Can you tell them? But you must not name me Granny. For I’m not. There’s no one to call me Granny, there never was nor will be,” she said. “But you’re safe here, I promise. Even if it is spring, now. Spring is the hardest time, when the armies have been emptied by the battles of the year before, and over the winter. Summer isn’t easy, for in summer they’ll take even a boy to fill up empty places, and he’ll never be seen again. A girl, too, poor thing— Don’t you think about it. There’s no ease in thinking on it. Autumn is dangerous, too, because what’s left then’s the soldiers who have lived through. Good soldiers fight and fall, as all know—the Captains live, and live, and live forever, while good soldiers die in their hundreds. Those that live—or hide away, as I’ve heard, in hay wains, or run away, I’ve heard, I’ve seen them sometimes, like wolves at the edges of the woods, some days. Winter is best, if you have shelter, if you have food, if you have fuel. Do you want to see my babies?” she asked, hopping up from the stool. “How did you come here? I watch the woods.”

Oriel didn’t know how to answer. He didn’t know what she was asking, and he didn’t think it mattered what he answered. But she was like a clay bowl that had been dropped on a stone floor, and shattered into pieces—and she made him uneasy. She wheeled around, standing in front of the bed. Blue veins stood out on her naked legs. Her hair straggled down over her shoulders. “You shan’t have my babies. Not one, not any, not boy nor girl, lass that will be, nor lad. I am their guard.”

Oriel looked at Griff, who spoke. “We came by boat,” Griff said, his voice quiet. “We came by water.”

“Then you must go away,” she said, “and by water. Go to an island. The islands are too far, far away, for the armies to reach, they’re afraid of water, they know nothing of boats. Go to an island and be safe. I’ve heard of one, an island all for boys, and the biggest boy cares for the others. The boys live, and farm, and fish, all together. There is no trouble among them. In storms they gather around the fire. The house is of stone, and it has many rooms, room for all the boys. In winter they stay inside, safe, warm, fed. In troubles, the biggest boy settles their troubles for them, the biggest boy decides, and when he gets too old he goes away. Because it’s men who make soldiers, and battles,” she confided. “Not boys. Would you eat some bread?” she asked. “Sit, let me feed you. There’s the bed, there’s the floor. Are those fish? Tell the men of Selby, from me, I thank them for the fish.”

Oriel tried to tell her, again. “We didn’t come from Selby.”

“Once the sun sets we can have a small fire, just a little one, just enough to cook a fish over. Meanwhile,” the old woman said, “there’s bread. It makes you sick to eat fish uncooked, lads sometimes don’t know that.”

She brought a round loaf down from the shelf and held it against her chest while she sawed off pieces with a long knife. Oriel sat beside Griff on the floor, their backs against the door, their legs pulled in close because there was no room to stretch them out. She gave them bread, which filled his mouth with its taste and its promise of sustenance, and he thanked her.

“Men of Selby keep me supplied with bread. For if they don’t, what if I were to return to my houses? When my man left,” the old woman said, “he left me with my three houses all in a row, one to live in with my babies and the other two for my keep. He said, he couldn’t stand the babies. He said he was sick of the babies. As if he had no idea how babies get into a woman’s belly, for all the babies he’d gotten out of my belly? This was before. Before they said I had to leave, before they told me to go away, before they moved me into this house and brought me food. The men of Selby know the soldiers will come here first, whenever the soldiers came this is the first place, and they took my babies. The soldiers came and took them. This, I swear it to you, this the men of Selby knew. I hold them responsible. They can’t deny it and they will. But they’re afraid. Of me. As much as they are afraid of the soldiers. The soldiers aren’t afraid. How did you get here? I watch the woods.”

“By boat,” Griff said. “We came by boat.”

She nodded silently and after a while her eyes closed and her head fell forward onto her chest. The smell of fish filled the room. Oriel looked at Griff. They rose to their feet.

But as soon as they moved she was awake, and standing. “Time for the fire, it’s safe now. Come, you—” she pointed at Oriel, “there’s tinder ready, you start the fire and you—” she pointed at Griff, “we’ll bring the babies out.”

They could have left the house, and easily. Oriel knew that, but he chose not to. There would have been no difficulty in pushing her aside, lifting the bar on the door, and returning to the boat. Once they were out of the house she couldn’t have caught them. But there was something fearsome to her, and he feared it. What he knew of fear was that you had to know its face, or it would drive you the way it wanted you to go.

Also, he thought, blowing on the sparks in straw to bring the fire to life, there was something in her madness—because he had no doubt that she was mad—that was so weak he didn’t want to hurt it. She was like the fish he’d pulled out of the water, gasping for air before he took pity on it and smashed its head with a stone.

An old woman was different from a fish. You couldn’t just smash in an old woman’s head, no matter how much that seemed the only kindness you might do her. Not as if she were a fish. Not when she was too mad to know what she was.

“It’s too soon! Too early for the babies!” she shrieked now. “You can’t go near them, I’ll stop you!” She beat at Griff with her hands, without even making them into fists.

Griff backed away, his back to the door, and slid down to where he had sat before. The old woman stood panting over him, then turned around to look at the bed, then turned back to the fire.

“Good lads, good lads,” she said. “How did you get here?”

Oriel answered her again, his voice calm, as the fire flamed among pieces of wood as thick as his wrist, growing steadily warmer and brighter, “We came by boat.”

“Lads are good. I believe. It’s soldiers are bad, and men, because you can’t make soldiers out of lads. I believe. I wish I were sure.” She had hunkered down by the fire beside Oriel and her hair shielded her face like a greasy white curtain. Then she seemed to see the fire, as if

she hadn’t known it was there. She pushed herself up, her hand like a claw on his shoulder, picked up the netful of fish and dumped it all onto the flames.

The fire hissed. Smoke rose. Fish lay like seaweed over the fire. There were no coals yet, to burn on beneath the layer of fish. The fish hadn’t been gutted. There wouldn’t be much eating here, unless you had a taste for undercooked ungutted fish.

“Let me show you my babies,” the old woman said. “Both of you, good lads both, come—little birds in the nest, my little birds in the nest where they are safe—” As she spoke, she got down onto her hands and knees and pulled out from under the bed a long flat wooden box, covered with a blanket.

“Hush now. You must be quiet for now they sleep. All the pretty little birdies, asleep.”

Oriel bent down, looking over one of her shoulders. Griff stood at the other. Kneeling beside the box, she folded back the blanket.

A row of sixteen bundles lay in it, each one wrapped tightly around with cloth, each about the size of a six-month shoat. The old woman reached in and picked one up, cradling it in her arms.

The doll-baby she cradled crackled in her embrace, like a straw mattress. Some of the doll-babies were formed from branches, he saw, and some from field grass, and some—he averted his eyes—looked like human babies, only old and dried up like salted fish. Over the old woman’s bent head, his eyes met Griff’s.

“Forty-one winters hang off my shoulders now,” the old woman said, her face turning from one of them to the other. “Oh but there was a time . . . I birthed my first babe when I was fourteen summers. He was to have my man’s basket shop, this son of mine, and the tools, and the withy brakes down by the river, all was to be his when he grew. But he got the summer fever, but there were other sons by then, to have the shop and tools and learn the weaving ways, but one went to be a soldier for Matteus and one to Karle and then, you see, the soldiers would come and bring their armies behind them, and they took the girls. So I hid my babies, and my man built this hiding place for them, this nest. You see them? They never give a peep. They know, my babies, they know this world. Or course, after my man left— He grew tired of the babies, the way men do. And I couldn’t stay in the town, with my babies. And they carried me out here in a cart, and gave me this house so that when the armies come south from Celindon there will be warning to Selby. They bring me my food, too. I’m old now. But I used to be—thirteen summers, and I was as young as you, a lass to your lads, and my breasts were round and white and sweet as moonflowers.” She pulled the doll-baby in close to her chest. “She’s safe now, from all of you,” the old woman said, hunched there.

Oriel told Griff, “Something must be done. Something, about this.” He didn’t know what he meant, but he felt it strongly. There was a fire in his heart. He didn’t know what he might do, but he felt—like wings spreading out underneath him, for flight—that he was the man who might do it. “Something.”

Griff understood him.

The old woman put the doll-baby back in place, folded the blanket back over the box, and pushed it back under the bed, with so much grunting that Griff and Oriel knelt beside her, to help. The wooden box scraped against the wooden floor, like bone against bone. Then she returned to the fire. She plucked at the fish. The top layer she dropped into a bucket, but those beneath she piled onto a wooden platter. “Eat,” she said. “I must eat to keep my strength up, to keep the watch,” she explained. “How did you get here?” she asked. “I watch the woods.”

“We came by boat,” Griff told her.

They picked the flesh of the fish off its springy bones. It tasted of the bitterness of the guts but Oriel, who had lived close enough to hunger to know how little the flavor of things matters, ate until his belly was satisfied. After it was fully dark, the old woman unbarred the door and let them go outside, one after the other—not both together because even in the darkness two might be seen, whereas one could slip through shadows unnoticed—to relieve themselves. Outside, under the starless sky, Oriel thought he could breathe again, and thought he would rather sleep the night in the open danger of the boat than the enclosed danger of the little house. But Griff waited inside, and so he had to return.

They lay wrapped in their cloaks on the dirt floor. The old woman had the bed, and her cloak became her bedclothes for warmth in the night. She talked long into the darkness. There was a Countess who never married, the lady Celinde, whose reign was long, longer than any others. The old woman had the babies Celinde could never have because Celinde never married, even though never marrying meant she could never have the babies a woman wanted. She had her lands, instead of babies. Now her lands were filled with soldiers who came to conquer and take food, and coins, gold, and silver, and copper, came like floods on the river, although some years the lands were spared. She learned to save the baby girls. She learned to control the baby boys, except for those who must go off to soldiery until the men of Selby put her into the cart, and her babies with her, and promised her that she would never hunger if she would keep watch on the woods. Ever since the Old Countess had died these many years ago when this old woman was barely more than a girl.

The old woman’s voice drifted like a low mist cloud above the room. Every now and then she would sit up in bed to ask, “How did you come here, lad?” One or the other of them would answer her, and then her floating voice would continue, and there would be names told, or memories of a dance, or memories of long winters under the bedclothes with her man before the soldiers came in the spring.

Oriel drifted into sleep and out of sleep, and then at last deep into sleep. A shriek seized him up out of it, and he was on his feet in the darkness with his throat beating.

Someone moved in the darkness. “I hear them!” The old woman’s voice cried like a seabird. “They move. It’s time, I must.”

Griff now stood beside Oriel, both of them ready for they didn’t know what from out of the darkness.

She unbarred the door and stood, a dark shape against a silver sky. “I will protect my own. If I am blooded and thrown down, I will rise again. Tell the people of Selby,” she said, and then turned, pulled the door closed after her. They heard the bar fall down into place. “Safe now, you’re safe,” she called.

The voice moved away, faded away. They were left in silence and darkness. For a long time, Oriel didn’t speak, and Griff waited for Oriel to speak first, as if Oriel would have the better measure of their hazards.

Oriel waited. Almost, he thought he could hear the sound of distant chopping, but just as the sound became clear to his ears it ceased. He strained at the ears, to hear.

Griff’s soft breathing, his own heart, he heard those. At last he went stumbling through the darkness to where the window was, and pulled at the shutter. But it was sealed, somehow, and he couldn’t see to open it.

“What do you think she meant?” Griff asked. “Was it all madness? Some of those babies—” Griff didn’t finish the thought.

Oriel struck sparks to light the candle. “I’ll be happier to be away from here.”

“If any of what she said had any part of truth, and I think some or all of it must have, I’d go mad, too,” Griff said.

Oriel pulled the bolt back, and opened the shutter a crack. He could see the deep blue sky of coming daylight, before the sun had appeared but after the night had withdrawn from the field. He could hear nothing except the sniffling of wind. He could smell no fire. He had led Griff outside and pulled the door shut behind them before he understood what it was that he hadn’t seen in the emptiness before them. The meadow grasses bent towards the silvery water.

The darkened woods waited on all sides, thick as hills.

“I don’t hear her,” Griff said. “Do you think there was an army? How long since she left us?”

“Long enough,” Oriel said. His mind was already busy on the problem, thinking it out, to travel north or south, or inland, what unknown dangers might await in every direction, and what known dangers. He didn’t know en

ough—of the land, of the people, of the times. He couldn’t even choose well. But there was no help for that, and no use to regret. Once it was light enough to see, he could at least see an immediate danger.

“Where are we going?” Griff asked. “Where’s the boat?”

“Gone,” Oriel answered.

“But—?”

When they had the boat, they were free as birds, Oriel realized. When they had the boat, they could have eluded many dangers. Now, they had only their wits, and their feet, and luck.

“Why would she do that?” Griff asked.

“I think, she will have thought she was protecting us. Because the boat could be seen,” Oriel said.

“Now what?” Griff asked.

“West,” Oriel said. “Celindon lies to the east—remember?”

“Yes.”

“I think she was saying that the armies will stop at Celindon, for its riches. There are gold mines in the hills of Celindon,” Oriel said. “So Selby, and south, is the better choice.”

“Do we go along the coast or through the woods?”

“I think there should be a path into the woods, if the town brings her food. I think that will be the quicker and safer way.”

They crossed the meadow in growing light. The grass whispered like water at their boots. It was Griff who spotted the dirt path emerging beside a fat beech tree, whose branches spread out over the path like an arched doorway.

Oriel, with Griff behind him, moved into the deeper darkness of the wood.

Part II

The Saltweller’s Journeyman

Chapter 8

ORIEL LED AND GRIFF FOLLOWED far enough behind to stay clear of the back-snapping branches. Although worn down to dirt by frequent use, the path was no wider than a solitary man would need. All around, the woods were crowded with tree trunks, and tangled with undergrowth through which, occasionally, great grey boulders pushed their way. From overhead, sunlight sprinkled onto the little new leaves and flowed down over the long branches of firs to lie in bright patches on the path. It was cool, in the woods, and shady. Their progress was steady. They tramped—

The Runner

The Runner By Any Name

By Any Name Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do?

Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do? Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things: Mister Max 1

Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things: Mister Max 1 The Wings of a Falcon

The Wings of a Falcon Bad Girls in Love

Bad Girls in Love Toaff's Way

Toaff's Way Building Blocks

Building Blocks Orfe

Orfe Tell Me if the Lovers Are Losers

Tell Me if the Lovers Are Losers It's Not Easy Being Bad

It's Not Easy Being Bad The Book of Kings

The Book of Kings Dicey's Song

Dicey's Song A Solitary Blue

A Solitary Blue Tree by Leaf

Tree by Leaf Sons From Afar

Sons From Afar Teddy & Co.

Teddy & Co. Jackaroo

Jackaroo Elske

Elske Izzy, Willy-Nilly

Izzy, Willy-Nilly Come a Stranger

Come a Stranger Mister Max: The Book of Secrets: Mister Max 2

Mister Max: The Book of Secrets: Mister Max 2 Seventeen Against the Dealer

Seventeen Against the Dealer The Callender Papers

The Callender Papers The Vandemark Mummy

The Vandemark Mummy Tale of Birle

Tale of Birle Glass Mountain

Glass Mountain The Tale of Oriel

The Tale of Oriel The Book of Lost Things

The Book of Lost Things The Book of Secrets

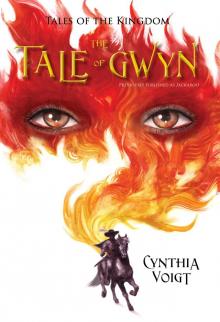

The Book of Secrets Tale of Gwyn

Tale of Gwyn