- Home

- Cynthia Voigt

The Book of Lost Things Page 9

The Book of Lost Things Read online

Page 9

He had entirely forgotten about his tutorial appointment.

A faint pounding sound, like a rubber mallet landing over and over again on a chunk of wood, reminded him. He dashed around to the front of the house, where a tall redheaded man knocked and knocked on the door.

The man looked older than Max had expected. He looked like a university graduate, not a university student. He wore a dark blue cardigan sweater under his brown jacket and a fedora on his head. His ill-fitting trousers were a light brown, and his boots were worn down at the heels. His briefcase looked softened and scraped by hard use. However, when he turned to look at Max, his eyes were a lively bright brown. Also, the man was entirely handsome, like a marble statue of one of the Greek gods, Hermes, perhaps, or Apollo. “You must be the grandson,” he said.

“I must and I am,” Max answered. “Are you Ari?”

“The mathematics tutor. Let’s get to work. I’m on a tight schedule.”

Max led him around to the back door, wondering what the man would say about his skyscape, but the tutor didn’t even look at it. He seemed unaware of the easel and the garden, unaware of anything other than his immediate business. Inside, he went right to the little kitchen table and opened his briefcase to pull out his books and papers. “I hope you have a pencil? Paper? Sit here.”

Ari was treating Max like a little boy, so “First I’m going to make a pot of tea,” Max announced.

“Oh.” The tutor turned to look at him again. “I take mine with milk and sugar, if you have them,” he said, now as much a guest as a teacher, which was Max’s plan. It wasn’t just Grammie from whom his independence needed protection, he thought. It was everyone.

Max filled the kettle with water and set it on the stove. He pulled down teacups, the sugar bowl, and the small pitcher for milk, at the same time telling Ari, “I know all the functions. Add, subtract, multiply, divide. There’s bread and jam, would you like some?”

The tutor took a few seconds before answering, a shade of reluctance in his voice, “Yes, I would. Please. I don’t seem to have had any lunch.”

From the look of him and the way his eyes lingered on the loaf of bread as he waited for Max to cut slices, Max guessed he hadn’t had any breakfast, either. But why should a university student who was so well spoken and so tidily, if shabbily, dressed, and also had fine manners, go without food all day?

Ari, however, couldn’t be asked that question because he set to work tutoring, even as he ate slice after slice of bread and jam while drinking cup after cup of tea enriched with milk and sugar. He had Max sit down beside him at the table and tested his student’s claim about addition and subtraction, multiplication and division, at the end setting him a difficult problem in long division. “I guess you do know the functions,” he concluded. “Good. You’re someone whose self-evaluation can be trusted. Good again. What about fractions?” and he emptied his teacup. He seemed, at last, to have eaten enough, and in fact only the heel of the bread remained.

Max worked a page of fractions, adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing, while Ari watched, nodding every now and then.

“Good for the third time. So we can get right to work on geometry,” Ari said. “Geometry’s my favorite part of math. Everything makes sense, everything can be proved, everything has a place and a purpose. Unlike the world we live in,” he added, in the tone of voice with which people greet an idea they have to admit is true but wish weren’t. He pushed his plate aside and opened one of his books, Euclid’s Elements, Vol. 1. “Triangles, parallels, and areas,” he announced. “Definitions first, of course. If you want to learn something, you have to know the vocabulary. Let’s see how adept you are at memorizing, shall we?”

Max didn’t mind this one bit. He enjoyed using his brain. One of the things he liked about acting was the work of memorizing lines, and just as much as setting colors on paper, he enjoyed figuring out how to put together a painting. Even schoolwork often interested him.

Ari opened the book between them on the table.

From the very first definition, “A point is that which has no part,” Euclid required close attention to exactly what was said. Ari had Max first read the definition aloud and then draw on a piece of paper exactly what the words meant. In this situation, Max was happy to do as he was told. There was something about envisioning parallel straight lines, “which, being in the same plane and being produced indefinitely in both directions, do not meet one another in either direction,” that pleased him with its precision. At the end of the lesson, Ari wrote down each of the words on a sheet of paper and asked Max to write as many of the definitions as he could remember. “You won’t get them all, not yet, but let’s just see how you do,” he said.

Max set to work, trying to remember Euclid’s exact phrasings. For several minutes, the only sound in the room was the scratch of his pencil on the paper, then that was joined by a deep, regular breathing. Max looked up to see that Ari had put his head on the table and fallen asleep. Max studied his profile, the longish, proudish straight nose, the dark curve of eyebrows, the strong jaw. He thought that Ari awake looked older than Ari sleeping, and returned to the definitions.

When he had written as many as he could remember, which was only twelve out of twenty-three, he set his pencil down on the table. As if he had only been waiting for that small sound, Ari sat up, eyes alert. “Done already? Let’s take a look.” He reached out.

Max kept his hand on the paper. “You’re overtired.”

Ari didn’t argue. “I’ve learned to take catnaps. They say Napoleon did that. And he was always fresh, always ready to run a country or fight a battle.” Ari smiled then, a subdued smile, just a lifting of the corners of his lips, as if he didn’t think he had the right to smile brightly, or widely, or entirely happily. “I’m not Napoleon, you may have noticed? I don’t want to be a Napoleon, either, even if I do have …” He did not complete that thought. “The truth is that I have too much work, two regular part-time jobs, plus whatever I can pick up tutoring, plus the university courses. Life’s expensive,” he told Max. “Textbooks are expensive, too.”

Max knew how to solve this problem. It was pretty simple, after all. “Couldn’t you take fewer courses?”

“I could, but here’s the difficulty: I’m already only taking two courses a year, and I need the degree as much as I need the money. I save most of what I earn for …” Again he let the thought drift off and rephrased it. “I need to save most of my earnings. There’s a specific sum I need to have, and I’m almost halfway there. The only un-minimal expense I have is housing. In order to keep to my schedule I need to be close to the University, and housing in the New Town is expensive.”

“How much do you pay?” Max asked.

“Forty a week. I have my own room. Weekdays I wash dishes at a restaurant near the City Hall, the midday shift—I can eat there those days—and three times a week I’m the night clerk at a hotel near the University. I can study then, too, because almost nobody comes in after midnight, and I kill two birds with one stone, as they say. Which is pretty Napoleonic,” and he smiled again, that same subdued smile. “I guess that’s more than you want to know.”

Max relinquished his paper and watched the tutor read over it. “You’re working hard,” Max remarked, and then asked, “Do you do well in your classes?”

“Quite well sometimes, and others well enough. You’re a pretty curious fellow, aren’t you? This”—he put a finger on the paper—“is not bad, not bad at all. A good beginning. I think I’ll enjoy teaching you, but now,” and he got busy packing up his books, selecting from his papers a sheet on which he had copied out all twenty-three of Euclid’s definitions, “I have another student to see, calculus, and he’ll be waiting at the library, which is a half hour’s walk, so if you’ll give me my fee— What are you paying, by the way?” he asked, and took a small notebook out of the briefcase. He uncapped a pen.

“Ten,” Max said, taking his purse out of his pocket. “But—” He

was busy thinking about Ari’s financial difficulties. “But why—?” He didn’t know how to ask this question.

The tutor paid no attention. He opened the notebook and found the page he was looking for, which was already lined with two columns, headed with names that Max couldn’t read from where he sat, and numbers beneath the names.

“What are you saving up for?” Max asked. “Why do you have to have a degree?”

Ari looked up. He ran his fingers through his dark red hair. “Oh,” he said. “Well.” He shrugged. “I made a mistake, years ago, and … Well, I lost everything of value that I had, but I was a spoiled young man and it served me right. The bad part is I cost somebody else everything, somebody who had much less to lose than I did, so her everything was much more valuable.”

“Very mysterious,” Max observed, hoping to hear more.

Ari ignored the hint. He wrote the figure 10 in the numbers column. “What’s your name?” he asked. “I have to pay taxes on what I earn, so I have to keep records, and I can’t just put down Grandson.”

“Mister Max,” said Max, wishing again that he could say Bartholomew or Lorenzo, since he wasn’t sure how far he could trust this tutor, although he did instinctively like him. And Grammie had approved him, too. Max did, however, have an idea about a way to solve at least one of Ari’s difficulties, and one of his own at the same time. “Why don’t you have a room here, in exchange for the tutoring,” he suggested.

Ari shook his head. “It’s a long way from the University, and the hotel, and the restaurant. Not to mention the library.”

Max had an answer to that: “There’s an extra bicycle in the cellar.” His father liked to take early-morning rides beside the lake. Max told Ari, “You could use that one. I ride mine everywhere, and it only takes twenty minutes by bicycle to get almost anywhere in the New Town.”

Now Ari was tempted. “What would your grandmother say?” he asked.

It was what his grandmother was saying that Max was trying to avoid. “Grammie doesn’t live here. She has her own house, the one across the back garden, behind this one. I live alone,” he told Ari, “so it’s up to me, not her. There’s a big room upstairs, a worktable, too; you could save that forty a week, which would be actually only thirty since I won’t be paying you for lessons, but still, thirty is something.”

“Thirty is a lot,” Ari said. He looked around the kitchen.

“I have dinner with my grandmother every night, so you’d come, too.”

“Let me think about it.”

“She’s a really good cook,” Max could promise him.

“I once knew a really good cook,” Ari said, and Max knew then that the tutor would move in and he’d solved the problem of Grammie not wanting him to live alone. It made him feel good to know that at the same time he’d solved a bit of Ari’s problem. In fact, Max felt pretty pleased with himself, and clever, too. He felt so good that he immediately thought of two new ideas about how to address the problems with his windy skyscape and was impatient to go back outside and try it again.

“My rent’s due tomorrow,” Ari told him, standing up. “I pay Wednesdays, a week at a time, in advance.”

“Then you better plan to move in here tomorrow,” Max said happily. William Starling was right, and Max was proving it: Twelve was old enough for independence.

In which Max is offered a job

After the satisfaction, and excitement, of earning that fifty, and the success of his plan to continue living in his own house, Max thought everything would be different. He thought his luck had changed. For the next few days, he walked confidently out into the morning. He always went by the Starling Theater to reassure himself that it was being safely neglected, and then made his way along narrow, winding streets and alleys of the old city looking for work. He went to Soapmaker’s Lane, Cobblers Way, Miller Street, asking at any kind of business. “I can learn anything,” he promised shopkeepers. “I can’t afford to hire you,” they answered, some apologetically and some angrily. “I have a family to feed,” they pointed out, or “Do I look that busy to you?” they asked.

At first, Max was un-discourageable. He talked to fishermen by their boats on River Way (“My wife mends the nets”) and the firemen in the firehouse on The Lakeview (“Our apprenticeships are all taken”). Some people made suggestions. “You should try at Bendiff’s factory. He’s a good employer, they say, if you don’t mind wearing a uniform.” “Icemen always need young men, especially now with summer coming on; those blocks are heavy for an older man.” “Have you thought of asking in the New Town? They have a lot more money there.”

Many wished him well, but by midday Saturday Max had still not found work. He had also spent most of his fifty. His parents had been gone for eleven days. Eleven days and no word! His spirits were once again sinking.

It turned out that he was glad to have studies. With the work Grammie and Ari assigned him, and with his painting, at least he always had something to do. Without them he would have had only worrying to do, about finding a job, about his independence, and about his parents. “You can’t give up,” Grammie advised him Saturday evening. “Not about anything.”

“I haven’t,” Max pointed out. “I won’t,” he promised, not entirely confidently. As long as he didn’t let himself start imagining all the nasty possibilities—William and Mary Starling trussed up in some dark mountain cave waiting to be ransomed, in chains in the dark and airless brig of a ship living on bread and water and headed where? for what purpose?—he was able to be patient, mostly. He could even hope, sometimes, that they were crossing some wide ocean in first-class luxury. In fact, he was pretty sure that they were captives and nothing worse. Because why would anybody cook up such an elaborate scheme just to murder them?

“No, I mean literally, you can’t. You have no choice. You have to find work.”

On Sunday morning, Max sat at the kitchen table with the book of Greek myths Grammie had assigned. It was pretty interesting, their idea of how in the early days of the world the old gods fought a huge battle against the younger gods to decide who was going to rule over the world and all the creatures in it. Max was thinking about this. Older people wanted things to stay the same, he decided, with themselves being more powerful and important than younger people, who hadn’t yet done anything significant or, really, difficult. Younger people, of course, wanted the older people to step aside, get out of the way, so they could have room to make all the changes they wanted, and improve things. Those gods were pretty extreme about it, the father swallowing his newborn children so they couldn’t grow up and overthrow him, the children cutting their father into pieces and tossing the pieces every which way so he couldn’t put himself together again and regain mastery. Max wondered if he felt a little bit that way about his parents, with his wanting to be independent. Then he wondered if his parents felt a little bit that way about him. These weren’t the most pleasant of thoughts, but they might well have some truth in them. Those Greeks didn’t sugarcoat things.

Grammie had asked him to write an essay in answer to the question “Which of the young gods would make the best king?” three to five pages in length, which struck him as unreasonable. After all, it would take only one word to answer. And he still had his geometry homework to do, which would take up the rest of his morning. After lunch, however, he hoped to spend some time painting. He could feel himself getting edgy, and painting, he knew, would calm him.

Max had every intention of starting out again Monday morning. He hoped that by then he would have had some idea, any idea … and then he did have one. A balloon man. Couldn’t he sell balloons at the park? Max wondered briefly how much it would cost to set himself up as a balloon man—it couldn’t be very much—then wondered, was that too far-fetched? It was the only idea he had. What if he never had another? What if he never found work? He felt himself becoming even more edgy. Which didn’t do any good at all.

So, instead of worrying about earning a living, he forced his attenti

on back to the Greek gods. He knew Grammie thought Apollo would make a better king than Zeus, but Max thought Athena was the best choice. Could a goddess be king of the gods?

By late morning, Max could put his papers into a neat pile, ready for the next lessons, and feel satisfied. He was prepared for his tutors. He still had coins in his pocket. He could go outside and paint. He’d work out front so Grammie wouldn’t see him and ask him to help her with some cleaning task or to come eat something or ask if he was feeling sad and worried, trying—the way she did—to make him feel as if nothing had changed. Even though things had changed, and of course he was feeling sad and worried. Partly. He was also feeling independent and eager, and curious about what might happen next to him, and he had a painting to work on. He wanted to try the stormy sky again, to see if he could use darker shadows in the clouds—or maybe the shadows should be blue?—to make it look as if the wind was grabbing at them and pulling them to pieces. Setting the red beret at an artistic angle on his head, he put on one of his father’s worn, faded blue work shirts and carried his easel, its block of heavy paper clipped in place, out through the front door. He had both good light to paint in and an interesting problem to solve.

He was concentrating so hard on strokes and shading that the ringing of the bell startled him. His head jerked around and this made his hand draw a long black line right across the whole sheet of paper, from top to bottom, from left to right, from thick to thin.

The Runner

The Runner By Any Name

By Any Name Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do?

Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do? Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things: Mister Max 1

Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things: Mister Max 1 The Wings of a Falcon

The Wings of a Falcon Bad Girls in Love

Bad Girls in Love Toaff's Way

Toaff's Way Building Blocks

Building Blocks Orfe

Orfe Tell Me if the Lovers Are Losers

Tell Me if the Lovers Are Losers It's Not Easy Being Bad

It's Not Easy Being Bad The Book of Kings

The Book of Kings Dicey's Song

Dicey's Song A Solitary Blue

A Solitary Blue Tree by Leaf

Tree by Leaf Sons From Afar

Sons From Afar Teddy & Co.

Teddy & Co. Jackaroo

Jackaroo Elske

Elske Izzy, Willy-Nilly

Izzy, Willy-Nilly Come a Stranger

Come a Stranger Mister Max: The Book of Secrets: Mister Max 2

Mister Max: The Book of Secrets: Mister Max 2 Seventeen Against the Dealer

Seventeen Against the Dealer The Callender Papers

The Callender Papers The Vandemark Mummy

The Vandemark Mummy Tale of Birle

Tale of Birle Glass Mountain

Glass Mountain The Tale of Oriel

The Tale of Oriel The Book of Lost Things

The Book of Lost Things The Book of Secrets

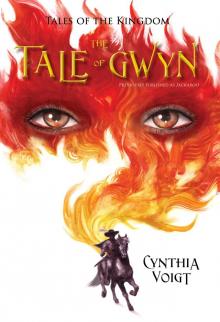

The Book of Secrets Tale of Gwyn

Tale of Gwyn